The airline industry pioneered the use of simulators.

Nov. 1, 2017

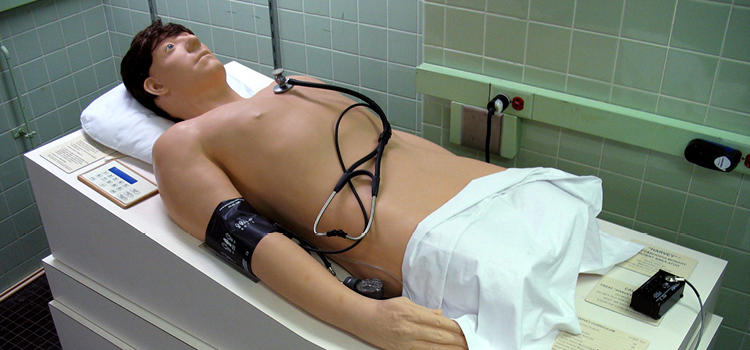

Harvey lies on his back, arms outstretched, palms up. His flesh-toned head lolls on the powder blue pillow, as the healthcare team hurries to stabilize him.

There is no family waiting nearby, anxiously sipping coffee, making calls. That’s because Harvey is a high-tech human simulator with 25 or so different cardiac functions of the human body. He’s here so the trainees working on him have the freedom to make mistakes and cause no harm.

That’s good news for you.

High-tech simulation is becoming increasingly important for training healthcare professionals who face dynamic situations requiring fast decisions – making them more adept for patients and their caregiver team members, say UCalgary experts.

Medical, nursing and veterinary students are learning through immersion, gaining hands-on experience in mock scenarios augmented with simulation technology. These allow them to safely practice responding to medical situations.

In UCalgary’s Cumming School of Medicine (CSM), specially designed human simulators such as the Harvey – a lifelike cardio-pulmonary simulator loaded with voice capability, real heart and lung sounds, pulses and blood pressures, among other features – allow students to work in realistic clinical settings overseen by experienced faculty members.

The airline industry pioneered the use of simulators.

The airline and engineering industries pioneered the use of simulation in safe and controlled environments. Flight simulators with visuals, sound and movement became available in the 1950s. The technology has since evolved and the use of different types of simulation in healthcare has followed suit. The University of Miami developed Harvey and it's been used in medical centres for more than 45 years.

As the use of simulation has spread across various industries and spurred advances in education, programs that include simulation at UCalgary have grown, in some cases not just keeping pace, but leading it.

UCalgary operates one of the leading undergraduate medical education simulation programs in the world. The program includes two Harveys programmed with 31 clinical presentations and findings and it has expanded to include two wireless SimMan3G simulators.

“One of the major aims of simulation is to reduce the potential for medical error,” says Dr. Lisa Welikovitch, the CSM's associate dean, Postgraduate Medical Education (PGME). “Our aim is to be at the forefront of this innovative approach.”

Simulation provides a one-two punch for health care. On the one hand, it provides an opportunity to evaluate how systems and the health-care team function. On the other, it enables educators and students to identify potential gaps that need to be addressed and minimize the potential for error.

Harvey the human simulator can simulate about 25 different cardiac functions.

So, is the use of simulation expected to usurp learning with live patients?

No. Simulation can be realistic, sure, but it’s not the real thing. In aviation, it’s one thing for a pilot to operate a flight simulator with theoretical passengers aboard, it’s entirely another when the aircraft is filled with squealing children and fraught parents.

Likewise, Dr. Welikovitch doesn’t expect the use of Harveys and other simulation tech to replace invaluable clinical experience with real patients in emergency rooms or on hospital wards.

Instead, she foresees a comprehensive education in postgraduate medicine including both as complimentary experiences, so that residents can develop the knowledge and skills required to practice independently.

“The number of programs using simulation is growing,” says Dr. Welikovitch. “Let’s consider postgraduate programs – many have developed robust simulation teaching elements and incorporated them into residency training. Moving ahead, we’re going to see programs continue to explore innovative strategies.”

Simulation in medical education lets trainees develop a range of competencies in a safe environment, including problem-solving, specific technical skills and the management of medical and surgical emergencies.

Dr. Welikovitch says simulation exercises also allow instructors to observe students in action, and provide guidance afterward. “Feedback is an essential part of the learning process,” she says. “A debrief allows the learner to reflect on the experience. They can consider the ways in which the lessons learned will influence their future practice.”

The state-of-the-art Advanced Technical Skills Simulation Laboratory (ATSSL) at UCalgary is a resource for both students and trainees. PGME hosts annual simulation symposiums, which feature guest speakers who are leaders in this field.

Simulators help nursing students develop skills and confidence in clinical settings.

For the past seven years, hundreds of future registered nurses have built their self-confidence and competence at the Clinical Simulation Learning Centre (CSLC) in UCalgary's Faculty of Nursing, where simulated scenarios such as cardiac arrests reflect the high-pressure situations they’ll face on the job.

Step into the CSLC and it’s a dizzying array of high-tech features that include 53 basic patient care environments, three simulation suites, three control stations and three debriefing rooms. You might see a group of three nursing students around a simulation patient, working swiftly while experienced faculty members adjust the patient’s heart rate, voice and responses from behind a two-way mirror.

Is that blood on the floor? Moulage – a French word for casting or molding – can be used to heighten realism. The use of lifelike substances, lighting, sound and even smells can make the moment more immediate, engaging nurses more deeply in their training.

Sandra Goldsworthy, an associate professor with a dedicated research professorship in simulation, saw the benefits of using simulation early as it began to gain traction in healthcare education.

“My first foray into simulation was with critical care simulation and the preparation of registered nurses to transition to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU),” says Goldsworthy, whose simulation in nursing research role was pioneering when she came to UCalgary three years ago.

“I knew simulation was a game changer when I heard the reports from the practice areas and the transformation they had seen in practice during orientation. This was an ‘aha’ moment. I saw it was working and it was backed up with evidence.”

What are the payoffs of using simulation in health-care education for students and for patients in the wider community?

“In the end, the patients can receive higher quality, safer care,” says Goldsworthy. “The students are fully engaged in this type of education and get very excited. They stand at the door and can’t wait to get in. It’s proven effective in improving their performance and knowledge.”

Repetition is key to the success of immersive learning, she says, so the ability to pause, then repeat scenes enhances skills mastery.

Goldsworthy and her team are aiming to improve nursing competencies. Their studies underway include reducing medication error through simulation, recognizing and responding to the deteriorating patient, assessing the impact of booster training on CPR performance, the use of virtual simulation and more.

There are different types of simulation. One is the use of so-called human similar or high-fidelity patients, which have high-tech bells and whistles, such as the capability of presenting mock seizures. Another is using human patient actors, called “standardized patients.” A third is virtual simulation, an emerging field.

“The first two types of simulation are hands-on and right in front of you, but with virtual it is online and you drive the scenario,” says Goldsworthy. Predictions for the future include more immersive simulation experiences and the use of holograms to instantly provide patient practice experiences. “The ultimate goal is providing the safest quality care to patients.”

Animal simulators are used in veterinary education.

UCalgary’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (UCVM) uses innovations in 3D printing in simulation training. One example is the back half of a dog – 3D printed from CT scan data – that makes learning how to do epidural injections easier for veterinarians.

UCVM associate professors Dr. Mark Ungrin and Dr. Matthew Read oversaw the creation of the simulator in a collaboration with UCalgary Biomedical Engineering (BME), including then-undergraduate biomedical engineer Douglas Kondro (now a member of the University's BME graduate program in Ungrin's lab).

“Rapid prototyping technologies such as 3D printing allow the structure of a simulator to be taken directly from real medical scan data," says Ungrin, "particularly when partnered with techniques such as replica moulding that allow the resulting structures to be transferred to a broad range of materials with the desired properties.

“Features can be fine-tuned to make them more or less obvious, easier or harder to hit with a needle during a simulated procedure, and so on, depending on the skill level and experience of the trainees.”

Reaching out to help in the wider community can integrate service with immersive learning in yet another type of simulation. It benefits the public as well as the students who are training, says Serge Chalhoub, senior instructor, Veterinary Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences.

A UCVM partnership project with the Calgary Urban Project Society (CUPS) gives third-year vet med students the chance to use the skills they’ve learned in the classroom while under close supervision, participating in free veterinary clinics for pets of people who live below the poverty line. Championed by Chalhoub and fellow UCVM faculty member Dr. Jack Wilson, it has worked so well as a pilot project that it’s now a regular part of the curriculum.

“Learning by doing is extremely powerful,” says Chalhoub, who aims to do research that will show the benefits of this program. “Students must balance talking with the client, doing a physical exam and making recommendations while practicing all of the communications skills that are an aspect of higher learning.”

Other sim pieces within the UCVM four-year program include using actors as animal-owning clients, who are playing a part – perhaps they present as an owner who is telling the veterinarian that their dog is not well and they don’t know what to do. Also, virtual animal patients in computer sims might require a student to, say, listen to abnormal heart sounds and properly respond.

Cindy Adams, a professor who directs the UCVM Clinical Communication program, came to Calgary in the early 2000s to do an internship because a colleague used sim patients in medicine. In 2006, she brought forward the idea of using simulated clients within UCVM to integrate content and knowledge – with a strong emphasis on communications.

Adams has co-authored the new book Skills for Communicating in Veterinary Medicine, published by Otmoor Publishing, Oxford and Dewpoint Publishing, New York. The book provides upwards of 900 references that support the importance of clinical communications competency in veterinary medicine.

For example, a veterinarian requires deft and delicate communication skills that can be put to the test in the most trying way. Saying goodbye to a family pet is something most pet owners dread, but it’s become a part of most veterinarians’ lives. The UCVM helps to ready its students with an end-of-life laboratory that demands much of them, but readies them for the working world.

“The end-of-life lab that we do is highly immersive, deep, emotional learning,” says Adams. “it’s a tough lab. Not many schools want to tackle it on such a deep level. Here, we are very passionate about what we do.”

– – – – –

Participate in a research study

– – – – –

Dr. Lisa Welikovitch, MD, is the associate dean, Postgraduate Medical Education (PGME) in UCalgary's Cumming School of Medicine. She is an associate professor in the Department of Medicine and a member of the Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta. Her main areas of interest are Echocardiography and medical education. Dr. Welikovitch has served as educational director for C-SPIN (Canadian Stroke Prevention Intervention Network), responsible for programs that target trainees and junior faculty who wish to pursue clinical research careers.

Dr. Sandra Goldsworthy, PhD, is an associate professor in UCalgary's Faculty of Nursing, with a research professorship in simulation education. She is a recognized critical care expert, researcher and author or editor. Her research focus is on simulation and transfer of learning, job readiness and transition of new graduates into critical care, among her other areas of interest. Sandra is also a member of the O'Brien Institute for Public Health in the Cumming School of Medicine. Read more about Sandra

Dr. Mark Ungrin, PhD, is an associate professor and faculty member in the Department of Comparative Biology and Experimental Medicine in UCalgary's Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. The central theme of his research program is the assembly of cells into tissues and organs, particularly at the sub-millimetre scale. Read more about Mark

Dr. Serge Chalhoub, DVM, is a senior instructor at the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, in the Department of Veterinary Clinical and Diagnostic Service. He teaches Internal Medicine and is extensively involved in communication and professional skills at the UCVM. His research includes nephrology/urology and interventional medicine. Read more about Serge

Dr. Cindy Adams, PhD, is a professor who directs the Clinical Communication Program in UCalgary's Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and teaches in all three years of Clinical Communication Program/Professional Skills. She focuses on developing communication curricula in veterinary education and practice. Research interests include communication skills teaching, learning and assessment, and practice based implications in small and large animals. Cindy is also a member of the O'Brien Institute for Public Health in the Cumming School of Medicine. Read more about Cindy