UCalgary's nursing program focuses on community connections.

Nov. 1, 2017

Years ago, when Cydnee Seneviratne was a practising registered nurse, she found herself facing a dilemma. She had just finished treating a homeless man who'd had a stroke and was discharging him from the hospital. The problem was, she didn't know where to send him. "I put him in a cab and told the driver to leave him at the drop-in centre," she says. "It breaks my heart now but at the time, I didn't think twice about it."

Now associate dean (undergraduate practice education) in UCalgary's Faculty of Nursing, Seneviratne says students are taught a much different approach. Whereas in traditional nursing programs, where students learn clinical skills first, UCalgary's nursing education starts with community involvement, working with social organizations, day cares, seniors and the like.

"Other programs tend to put their students in hospital settings first," says Seneviratne. "But we place ours with our community partners first. The advantage is that by the time they get to acute care practice, they use those community principles and theory to help inform their decisions. They would know what services are in place to help a recovering homeless person instead of sending them back into the street."

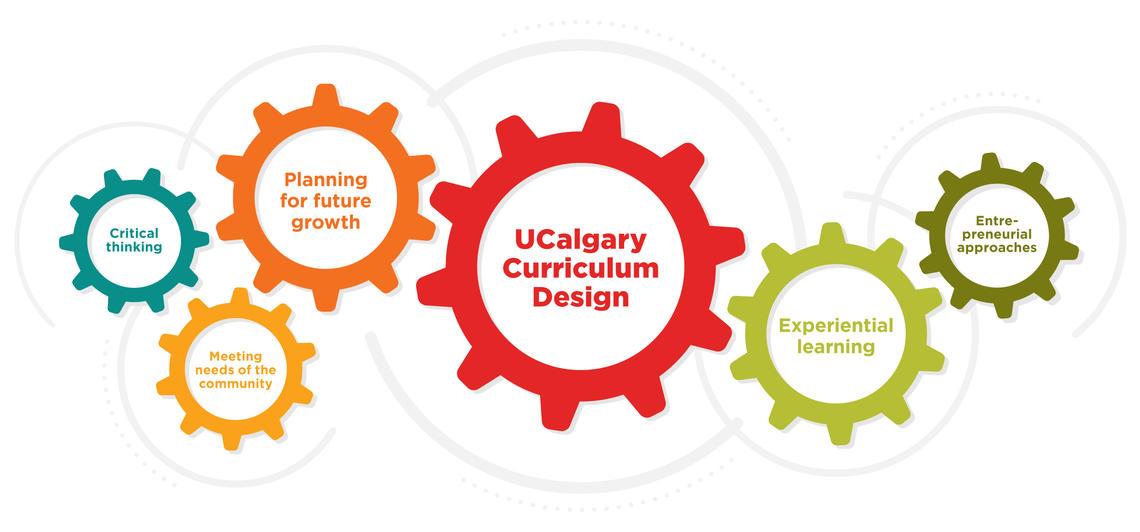

That type of community engagement is shaping curriculum development across UCalgary, where courses and degrees are tailored to address needs in the community and in the marketplace, from law to environmental design to nursing to business.

UCalgary's nursing program focuses on community connections.

According to Seneviratne, maintaining close ties with the community is key to understanding its needs, and there's no substitute for getting out into the field. "I'm our liaison with all our practice partners, whether it's Alberta Health Services, Covenant Health, or our community partners," she says. "I do my best to go everywhere that our clinical placements have been, and I meet them face-to-face. I'll ask them where our students excelled, and where there were maybe challenges, and what kinds of skills they need from our students."

The feedback Seneviratne gets from placement partners then results in adjustments to the curriculum, such as deciding when to teach students to administer drugs or set up intravenous drips.

Seneviratne says student placements work best when it's a two-way relationship, meaning the organizations where students get to practice their clinical skills also benefit. "It's a lot of work for them to take our students," she says. "We try to make sure we're giving back, so they receive something they need as well and we're not just taking from them."

Part of giving back involves sending students out into the community, along with instructors who are community health nurses, to identify potential needs and offer their services. "We assign them a zone for the city," says Seneviratne. "They go out and do a needs assessment of the community and if they identify a particular need, they approach the practice partner and say, 'we've identified this need you may have and if you do, we have students willing to work on this project for you to improve services in your community.'"

GEeMBA students travel to energy capitals around the world.

Naturally, in the business world, the approach is slightly different. Harrie Vredenburg is academic director of the Global Energy Executive MBA program (GEeMBA) in UCalgary's Haskayne School of Business, which gives students from around the world the skills and training they need to be leaders in the energy industry. Vredenburg says the creation of the program was driven mostly by market forces – and by his notion that the increasingly complex world of energy and environment required leaders with advanced understanding and skills. "I had completed a major energy policy project in Mexico for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and Pemex, the state-owned oil company," says Vredenburg. "I was asked how we could help train a group of managers with significant experience, who were ready to move into senior positions, but who they could not spare to go abroad for a full-time MBA. I had a sense that there was a similar need in other emerging economies dealing with energy. One of our MBAs was in New York with McKinsey Consulting and did a pro bono market study for us, and we determined there was a demand for this program internationally and in Canada."

"It's not practical for people to fly in from Mexico, or Nigeria, or wherever they are every other weekend to take classes in Calgary."

Vredenburg also says key stakeholders in the industry expressed interest in an executive program after the success of UCalgary's Sustainable Energy Development Master's degree (SEDV), which began with a focus on Latin America and the Caribbean, and trains students to manage sustainable energy projects. Vredenburg was academic director of the SEDV in 2006, when he was approached by representatives of the World Bank, who asked if he could replicate the program in Africa. "We got some funding from the Canadian International Development Agency," he says, "and we took an exploratory trip to Africa. We came back and presented our proposal to our dean at the time. He argued that we should think globally, and not restrict ourselves to this continent or that one. So we put our heads together and came up with the Global Energy Executive MBA."

Key features of the GEeMBA program were developed to address concerns and needs of the industry, says Vredenburg. "It's not practical for people to fly in from Mexico, or Nigeria, or wherever they are every other weekend to take classes in Calgary, as students would do in a typical executive MBA program," he says.

As a result, students complete assignments and attend classes online while working their regular jobs wherever they are in the world, and gather for two-week periods every three months in Calgary and other major energy centres: Houston, Doha, London, Beijing and Shanghai.

Vredenburg says this approach serves several purposes. First, students can have the flexibility to complete coursework around their lives and careers without too much strain from travel. Secondly, gathering every three months allows students not only to have intensive, hands-on learning experiences, including rich industry field visits in global energy cities, but they can get to know each other and network. Lastly, travel to major energy centres gives students the perspective necessary to be truly global executives. "When they get back to their home countries, they still have to work together in small groups online," says Vredenburg. "But because they've met and spent these intensive boot-camp periods together, they know each other, which makes collaboration easier. And they get exposed to different points of view. This close global relationship-based program network survives and thrives after the program too."

Sustainable development master's degree trains to manage large-scale sustainable energy projects.

The program that gave rise to the GEeMBA degree, the Master's in Sustainable Energy Development(SEDV), has similarly evolved in response to market conditions. Alastair Lucas, who, along with Harrie Vredenburg, is one of the co-founders of the program, says today's energy sector is far different than when the program first began in the 1990s. "Back then, the focus was much more on hydrocarbon energy," Lucas says. "The program has really seen a shift to the idea of a lower carbon energy future. There's no doubt we're in a transition, and it's really starting to pick up speed. The economy has gone up and down, and a lot of students in the program are people who started out in the oil and gas industry and are looking for knowledge that can either enhance their employability, or propel them into some kind of entrepreneurial activity, not just in oil and gas, but in renewables."

As the energy industry changes, so has the program material, developed in collaboration with industry and regulatory bodies. "We've been working increasingly with the firms on the renewable side," says Lucas. "Also the regulators, the Alberta Energy regulator for example. What they do has shifted somewhat as well, and our program reflects the shifts that we're seeing out there in terms of energy. We're seeing it globally, but we're seeing it particularly in Calgary where we've been so fixed on oil and gas."

"Now, just having an engineering degree isn't enough."

The curriculum of the SEDV program includes courses and workshops on ecology, chemistry, renewable energy, environmental assessments, pollution, law, human resources, indigenous culture and sustainability, among others. "There are 14 courses in 16 months, so it's fairly intensive," says Lucas. "The idea is to produce students who've had at least an introduction to a wider range of sustainability issues. They have a wider range of skills."

Lucas says the demand for graduates with those skills is increasing. "I've spoken to a number of people in the oil and gas industry who have said now, just having an engineering degree isn't enough," he says. "They're looking for people who have a broader range of skills. They have to deal with all kinds of environmental issues, with social, public and indigenous issues that they never had to deal with before, so they're looking for people who have some skills in those areas."

Non-traditional learning settings can help make course material more relevant.

A changing industry is also driving change in the curriculum in UCalgary's Faculty of Law. According to Dean Ian Holloway, there are two major factors contributing to an evolving legal profession. "It's the meeting of globalization and the technological revolution," says Holloway. "Those two things mean that the kinds of legal services that clients need – whether they're big companies or ordinary people – and the way they want to access those services, are changing. And if those things are changing, the profession has to change."

As a result, Holloway and his colleagues developed the Calgary Curriculum, a revolutionary approach to teaching law that aims to prepare students for a rapidly evolving legal landscape. Launched in 2015, the Calgary Curriculum includes intensive bootcamps to learn the foundations of law and basic legal skills, hands-on training in things like writing contracts, legal negotiations and drafting legislation, and clinical courses such as arguing mock trials in front of actual judges.

"We know a lot more now about how adults learn than we did in the 19th century."

One of the reasons for adopting this new approach, Holloway says, was the realization that the traditional method of teaching law was severely outdated. "If you took us and plunked us down in a law classroom from 70 years ago, most of us would feel pretty comfortable," says Holloway. "But we know a lot more now about how adults learn than we did in the 19th century, when the conventional model of legal education was developed. We know that adults learn best, and retain best, through intense exposure and the opportunity to engage. What I call the chance to roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty with ideas. What that means is that the old-fashioned method of legal education, three-hour lectures followed by go-for-broke, 100-per-cent final exams, has almost no pedagogical value."

In addition to courses designed around experiential learning, UCalgary law students are given opportunities to practise their legal skills for the benefit of the community. "We have a legal aid clinic called Student Legal Assistance, which is the norm in Canadian law schools," Holloway says. "But we also have a partnership with Innovate Calgary, where we provide free legal services to entrepreneurs. We have a public interest law clinic, which represents ideas or causes rather than clients. We run a Taxpayer Assistance Program, where our students help people who are having disputes with Canada Revenue and can't afford to hire a lawyer. We have an environmental law clinical program. A whole range of experiential learning opportunities to supplement what happens in the classroom."

Holloway says the Calgary Curriculum is also designed to introduce new ideas to students, and broaden the scope of their legal skills. "We've introduced a series of courses that no other law school teaches," he says. "Things like leadership for lawyers, legal project management, crisis communications. We have a seminar on the future of legal services, where we ask students to imagine what the profession will look like in 20 or 30 years. We're trying to be on the leading edge of designing new types of courses."

"It's our objective to prepare them for the profession they're joining, not the one we joined."

Preparing students for the future is the key to ensuring they can evolve with the profession, says Holloway. "The professional world is turning faster and faster," he says. "It's a pretty safe bet that technological progress is not going to slow down. It's a pretty safe bet that globalization, or interconnectedness, is going to continue. But precisely what kind of technology we'll have, or which international trade agreements we'll have, we don't know those things. So that's the challenge. It's our objective to prepare them for the profession they're joining, not the one we joined. But we don't know precisely what their profession is going to look like. That's what makes this so exciting."

Technological advances are forcing change in almost all industries.

Uncertainty over technological advancements and the future of the profession is common in the architecture, landscape architecture, and planning industries, says John Brown, dean of UCalgary's Faculty of Environmental Design (EVDS). And balancing the need to prepare students for the future with the need to provide them with the skills to work right now can be tricky.

"We're educating professionals for the next generation and beyond," says Brown. "We're looking into the future, trying to determine what a design professional is going to need to know, and at the same time trying to balance that with the requisite disciplinary skills that they need to work right now."

"We're educating professionals for the next generation and beyond."

One area of uncertainty is in digital fabrication. "We're very interested in how digital technology is being integrated into the built environment," says Brown. "We don't make cars the same way we did 30 years ago. That process has undergone tremendous change. Similarly, computers are automating parts of the building design process and robotic construction is starting to emerge. We challenge our students to think about what this could mean at a larger level. We want them to explore how this technology could create the kind of disruptive innovation in the design and construction industry that we have already seen with products like smartphones and services like Uber. That's the way culture is moving and we want our students to be at the forefront of this revolution as they build their careers.”

Anticipating the future and being able to adjust to it is a key component of the architecture, landscape architecture, and planning programs in EVDS. "Our students graduate with a set of skills," says Brown. "Some of those skills are obviously very practical and useful right now. But the most important thing they’ve learned is how to learn, and how to think about the future. It's about knowing how to react to the context that you're in, and being flexible, and knowing that those contexts are going to evolve massively over the course of your career. Rather than just learning a particular skill about how to draw something, or memorizing a specific building code, we want you to understand how buildings go together and how codes work. So drawing methods and building codes can evolve and do what they want, but you will still understand what they mean. We want to not only future-proof your education but give you the critical skills to be a leader in designing the disruptive, massive change our industries really need."

According to Brown, the future of education in general is moving toward preparing students for long term relevance, rather than just teaching them a particular set of skills they can use immediately. "The role of a university in times of great and rapid change is to make sure the people we're educating can understand and facilitate and manage that change," he says. There needs to be that flexibility and agility of mind to see what the problems are, and what are the potential tools that one has, whether it's an architect, or a doctor, or an engineer or a writer or whatever. It's not just learning how to do one thing, but how to do learn how to do things in an unknown future. It's much more complex to be a student now than it was 20 years ago, because it's not like we replaced knowledge, we just added more on, and they've got to get up to speed a lot quicker."

.

Regardless of discipline, the emerging trends shaping curriculum design are teaching students to plan for the future growth of their careers, and developing programs that meet the needs of the community.

"We're trying to educate our nursing students to think beyond the hospital," says Cydnee Seneviratne. "Registered nursing is not just in acute care, and that's not the future of nursing either. It doesn't matter which government is in, they all recognize that the best way to save money and resources in health care is to get people out of the hospital. You can't do that unless you have supports in place in the community, and the best people to do that are registered nurses who have a solid foundation in all aspects of health care."

Seneviratne says it's also time for registered nurses to start taking a more active leadership role in the community. "there's a lot of potential for nurses to be politically active," she says. "And that isn't about being aligned with any political party, it's knowing you have to lobby to get the resources you need for the population you're caring for. In order to do that, you have to think globally, nationally, locally. You have to think about your hospitalized patients, your client populations and what they need. You can't just go to work, put in your time, and you're done. Those days of registered nursing are over."

John Brown sees a similar leadership role in the community for design students. "Almost everything we do here is about disruptive change and social innovation," he says. "We recognize that the built environment, the natural environment, and a lot of our social context is, if not broken, seriously in peril. We can't continue to do the things that we do. It's just not sustainable, it's not resilient, and it's not socially equitable. So while we're teaching people how to design buildings, we're also, from a research level, integrating into our teaching this notion of disruptively changing the way in which the built environment exists. Changing the way cities are organized. Changing zoning so we can get secondary suites. Incorporating digital fabrication, so everyone gets to have a custom-designed house, not just the wealthy. That's what makes us distinct, that we're interested in the big questions, and how design can help answer them. It's not just about making pretty things."

For Ian Holloway, the connection between curriculum and community is direct. "By its nature, law only exists because of other social issues," he says. "Sometimes at law schools we can be justly accused of living in a hermetic bubble, but that's very wrong, because the only reason we exist is because real people have problems, and they need help solving them."

Participate in a research study

– – – – –

Dr. Cydnee Seneviratne, PhD, is the associate dean (undergraduate practice education) in UCalgary's Faculty of Nursing. She has been an instructor with UCalgary since 2001 and a registered nurse since 1991. Cydnee's academic interests include interprofessional practice/education, health services delivery, neuroscience and cardiovascular nursing. Read more about Cydnee

Dr. Harrie Vredenburg, PhD, is a professor in UCalgary's Haskayne School of Business and the academic director of its Global Energy Executive MBA program. He also serves as the Suncor Energy Chair in Competitive Strategy and Sustainable Development. Harrie's research interests lie in energy and sustainability. Read more about Harrie

Alastair Lucas is a professor in UCalgary's Faculty of Law and the academic director of the Sustainable Energy Development program. He is also an adjunct professor in the Faculty of Environmental Design. Al's academic interests are concentrated on regulatory issues related to energy and environmental law, oil and gas law, constitutional law, and judicial review. Read more about Al

Dr. Ian Holloway, PhD, is dean and professor with UCalgary's Faculty of Law. Before beginning his academic career, Ian spent a number of years in private practice, and was a member of the Royal Canadian and Royal Australian Navies for 25 years. His research interests include administrative law and legal history. Read more about Ian

Dr. John Brown, PhD, is dean and a professor of architecture with the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Environmental Design. His research interests include housing, aging-in-place, and architectural entrepreneurship. John is a registered architect and a founding principal of the architectural firm Housebrand. He is a recognized authority on residential practice and collaborates with medical and bio-medical engineering researchers to develop new housing options for an aging population. Read more about John