Medical students who learn in remote or rural communities often return to practise.

Nov. 1, 2017

From bringing mindfulness into the classroom to sending students out into the field, a growing range of innovative teaching practices is boosting teaching excellence. As more faculty try new ways to reach and engage their students, we’re seeing a wide array of benefits – from more medical students wanting to set up shop in rural areas to the next generation of veterinarians learning in the communities they will serve. Researchers are also digging into the right ingredients to create a high-performance team – for the classroom and the boardroom. Across UCalgary, faculty are dedicated to better understanding and improving student learning and they’re developing exciting new ways to do it.

Medical students who learn in remote or rural communities often return to practise.

Finding doctors to serve rural communities has been an issue for decades. To help solve that problem, the Cumming School of Medicine is introducing medical students to rural practice in a number of different ways through Distributed Learning and Rural Initiatives (DLRI).

“The underlying principle behind [DLRI] is social accountability and making sure we have the right mix of health care providers in the areas that need them,” says Dr. Doug Myhre, Cumming's associate dean of the DLRI. There are a number of opportunities for students, starting with Pathways to Medicine, a grade 12 scholarship where students who meet certain criteria are guaranteed a seat in medical school. Once enrolled, students are paired with mentors for the four years of undergraduate study before they reach medical school.

Starting in their second month of training, all students have options for rural learning experiences. In their final year, students can choose to do specific clerkships outside the city or spend the entire year completing their clerkship in a rural community. After graduation, the program supports rural-based family medicine residents and rural rotations for specialty residents – all of which adds up to more than 4,000 weeks of training per year outside the city.

"Many of them fall in love with the culture and values of the rural lifestyle."

The program is working. Medical students are entering rural family medicine training programs and establishing practices in rural Alberta once they graduate.

“They’re going to rural Alberta to do training and many of them fall in love with the culture and values of the rural lifestyle, the scope of practice and how much more they get to do,” says Myhre. “So they decide to practice and live in a rural community.” And those who decide to go back to the city have a better idea about the transportation and other challenges facing patients in rural communities.

The earlier and longer medical students are exposed to a generalist practice in a rural community, the more likely they are to choose to set up shop in a rural community themselves. And that’s good news for patients, like pregnant women.

“Women are having babies all over Canada. They’re not just having them with specialists in Calgary,” says Myhre. “People deserve and have the right to safe, competent medical care wherever they live in the country.”

When the UCalgary's Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (UCVM) was being created about a decade ago, the founders had a different idea about how to teach their students.

Instead of building a veterinary teaching hospital on campus like most other schools, they decided to send students to learn on the job with veterinarians at practices around the province. Since then, UCVM’s Distributed Veterinarian Teaching Hospital (DVTH) has become a model for new veterinary schools around the world.

Placing veterinary students in the community ensures they get hands-on practice.

“Our fourth-year students spend about 60 per cent of their time in the distributed model and 40 per cent on campus doing rotations with our faculty,” says Dr. Emma Read, teaching professor in Veterinary Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences. "They get the best of both environments.”

The model has many benefits. For one, a teaching hospital is very expensive to build and operate. Secondly, the hospitals tend to attract a tertiary referral case load – they’re sent cases that require special expertise or equipment to treat, and have often seen other veterinarians before being referred to the hospital.

"What they really need is to be exposed to good general practice cases."

“That’s great for the specialists but it’s not always great for the veterinary students,” says Read. “In most cases students are going to be general practitioners and what they really need is to be exposed to good general practice cases and learn how to look after things properly in the field.”

Students rotate through one or more of 54 practices and institutions in the DVTH. Faculty also work in the practices, providing community veterinarians with expertise and equipment. The community veterinarians play a crucial role on campus by helping interview prospective students, teaching professional or clinical skills and/or giving guest lectures.

“They’re engaged in the students’ education all the way through," says Read. "It’s not just about us sending students out to the community in final year, we bring the veterinarians into the students’ learning community much earlier and they work with the faculty as well. That’s been a very rich thing for the community veterinarians and for UCVM.”

When UCVM opened its doors it was the only veterinary school in Canada to use a distributed model – and one of only a few in the world (the model started at Western Health Sciences University in California and Nottingham University in the UK). Many new schools are following suit and even campus-based teaching hospital models are beginning to send students out to learn in the community. "Some of these places where they have a big hospital are starting to borrow from the distributed model,” says Read.

Meanwhile, back in Alberta, the distributed model is enriching students, community veterinarians and all of their patients. “It’s a win-win all around when you look at it.”

.

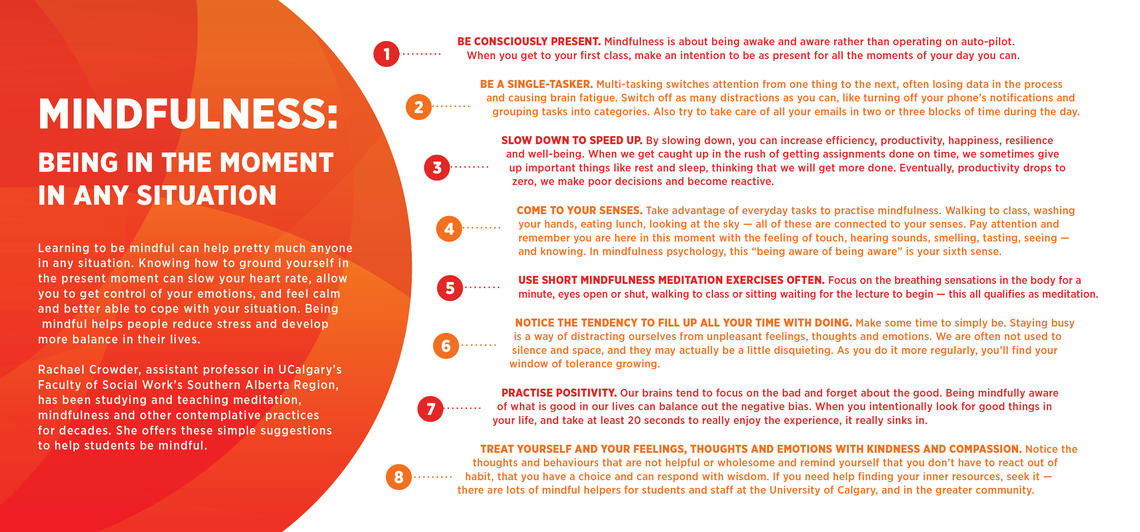

You may have learned to be mindful during yoga class, or practice ‘being in the moment’ while meditating in a quiet room. Now, faculty from a range of disciplines are learning contemplative pedagogy – using mindfulness and meditation in the classroom to help students bring their whole selves to the topic at hand.

“Contemplative practices help connect students’ inner world with their outer world,” says Rachael Crowder, assistant professor in the Faculty of Social Work’s Southern Alberta Region. “It’s how students can really connect their first-person experiences, not just their rational minds and critical thinking skills, but their feelings about things and a sense of ethics and justice into what they’re learning.”

Crowder is holding a series of retreats and workshops to teach more than 50 faculty from computer science to geography how to introduce mindfulness into their curriculum. An economics professor, for example, can talk about mindful consumption and ask students to think about the impacts of consumerism on marginalized workers halfway around the world. A geography professor may ask students to think of a place and reflect on how they feel when they’re there.

"We’re welcoming not only the students’ thinking capacity but their heart capacity as well.”

“It really makes it more relevant and meaningful for students when they’re invited to bring in those contemplative elements,” says Crowder. “Contemplative practices are not meant to replace critical thinking or rational approaches but rather to balance them, so we’re welcoming not only the students’ thinking capacity but their heart capacity as well.”

Social work students and other human service professionals have long been taught how to be mindful so they can help people in distress without burning out. “If we can help bring our clients and ourselves into the present moment it’s much easier to stay grounded and not get tossed by the waves of different emotions and thoughts,” she says. “It’s important to be completely present.”

Students in business, law or engineering will soon benefit from their teachers encouraging mindfulness. “We are coming together to talk about contemplative practices and problem-solving and ideas,” says Crowder. “We’re creating a kind of think tank.” And that all brain power is inviting students to use their hearts in class.

.

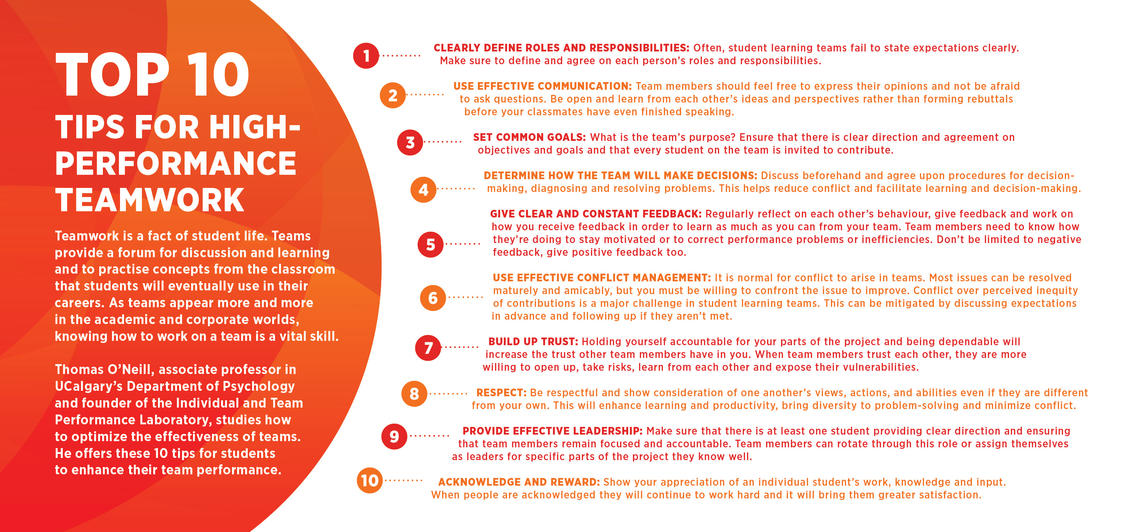

You likely think you’re a good team player. But chances are you could improve your team’s performance – at school or at work – with a better understanding of your individual strengths and weaknesses.

“Teams are a reality and we have to figure out how to make them work better,” says Tom O’Neill, associate professor in the Department of Psychology and founder of the Individual and Team Performance Laboratory. “We’ve done a lot of research that shows that almost no team really reaches its full potential.”

“Most people will think ‘I am a good team member,’ even those who aren’t."

The lab used that research to develop ITP Metrics, a free, online assessment tool that analyzes the “magic” behind a high-performance team. So far, 40,000 people around the world have taken the assessment to receive feedback, identify their strong and not-so-strong points and get recommendations on how to improve. O’Neill is using the metadata to learn more about how teams can reach their full potential.

“Most people will think ‘I am a good team member,’ even those who aren’t,” says O’Neill. “Really, teamwork is an ambiguous concept. It might mean something different for everybody, so when you get feedback on very specific teamwork attributes it helps you understand what high-performance teamwork is all about and how well you’re doing at it.”

The tool is used in corporate settings as well as post-secondary institutions to help students – and their teachers. “Instructors are using this tool because there is so much team dysfunction and conflict that they don’t know what to do about it and it’s wasting a lot of their time,” he says. ITP Metrics is also increasingly valuable for some faculties (business, engineering, medicine, nursing and science) that need to demonstrate their graduates have developed teamwork skills for academic accreditation.

While corporate consultants often charge exorbitant fees for team building advice, ITP Metrics, which is based on science, is free for any user. “I’d rather they use this than pay for something that some executive wrote based on one person’s experience that has no validity,” says O’Neill.

Participate in a research study

– – – – –

Dr. Doug Myhre, MD, associate dean of the Cumming School of Medicine's Distributed Learning and Rural Initiatives, has designed and implemented a number of rural-based medical education programs. In addition to his academic duties, he is involved in clinical care, spending half his time seeing patients. Read more about Doug

Dr. Emma Read joined the University of Calgary in 2007 as a clinical instructor in large animal surgery. As chair of the Clinical Skills Program, she led the development of this multi-instructor, multi-species hands-on training program. Read also served as the associate dean (academic) from 2015-2017, during which time she helped further develop the curriculum and assessment practices, and worked to standardize oversight and management of the Distributed Veterinary Teaching Hospital. Her research interests and scholarly activities are in assessment, simulation design and use, as well as clinical skills teaching and learning. Read more about Emma

Dr. Rachael Crowder, PhD, joined the Faculty of Social Work, Southern Alberta Region (Lethbridge) as an assistant professor in 2009. She is a registered social worker with decades of experience from grass-roots feminist practice with women who have experienced violence, including community organizing with sex workers. She is a meditation teacher and facilitates Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) and professional development training in mindfulness through the Faculty’s Centre for Professional Development. Read more about Rachael

Dr. Tom O’Neill, PhD, is associate professor of Industrial and Organizational Psychology at the University of Calgary. He is a leading expert in the areas of assessment, team dynamics, distributed teams, conflict management, personality, and flexible work. He is director of the Individual and Team Performance Lab and the Virtual Team Performance, Innovation, and Collaboration Lab. Read more about Tom