Dec. 1, 2018

Can a meal be medicine? How what we eat affects our gut health, which affects our wellness

We’ve all heard it a million times: ‘You are what you eat.’ From the Canada Food Guide to endless articles about nutrition, we’re told to limit the sugar, watch the saturated fats and make sure we eat lots of fruits and vegetables.

As researchers serve up more science about diet, nutrition and how it affects the bacteria in our intestinal tract — our gut microbiota, or microbiome — we’re learning that what we eat may help manage, treat and even prevent conditions from inflammatory bowel disease to obsessive compulsive disorder.

Eventually, we may see the day where diet and nutrition are incorporated into personalized medical treatments. Your doctor writes you a prescription for a specific diet consisting of foods that will interact with your specific gut bacteria to achieve better health.

“We’re learning that the same diet can have different effects on different people and we don’t know why that is,” says Dr. Maitreyi Raman, MD, author, clinical associate professor in the Department of Medicine at the Cumming School of Medicine (CSM), and medical director of the Alberta Centre of Excellence for Nutrition and Digestive Diseases. “It could be disease, it could be genetics or the underlying microbiota interactions. These are exactly the things that warrant more research.”

With new diets and nutritional fads appearing seemingly every other month, we've been trained to think of some foods as “good” and others as “bad.” There is general agreement that it’s better to eat fresh foods than processed foods, but even some foods considered “healthy” can be unhealthy for some people to eat.

“We can‘t be so blanket-like in our approach to foods and generalized comments about good foods or bad foods,” says Raman. “We have to understand, especially in the context of disease, how individual foods that are considered healthy still could have a role in disease progression.” Improving our health may come down to a personalized approach to what we eat.

Your gut and mental health

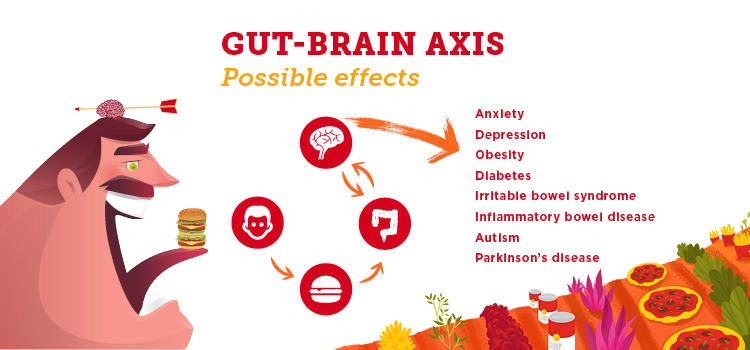

The intestinal bacteria in our gut have an impact well beyond our bellies. In addition to breaking down food, synthesizing vitamins and harnessing energy from carbohydrates, our gut microbiota communicate with our brains. We’re learning this gut-brain axis can play a significant role in our mental health.

“One of the things that researchers have identified in the last number of years is that there’s a link between our gut microbiota and our brain,” says Dr. Raylene Reimer, PhD, a professor in UCalgary's Faculty of Kinesiology and the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in the Cumming School of Medicine. “The bacteria in our gut make chemical signals that can act on the brain. It’s a two-way traffic communication system. They communicate with each other and thereby influence things like mood, depression and anxiety.”

Reimer and her graduate student, Emily Macphail, have begun studying how gut bacteria may affect youth who have been diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). The chronic condition causes people to experience intense worry over largely irrational concerns, such as being contaminated by household germs. People with OCD might perform repetitive actions, such as hand washing, to try to reduce the stress they feel from worrying about contamination by germs. As many as two per cent of Canadians will experience an episode of OCD over the course of their lifetimes and it’s uncommon for someone to recover from the disorder without some form of treatment.

“Our hypothesis is the bacteria in the gut might affect the behaviour in youth with OCD,” says Reimer, who is also a member of the CSM’s Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. “We want to look at the two-way path between the gut microbiota and the brain and specifically the metabolites that the gut bacteria are producing.”

Different types of bacteria produce different metabolites, or small molecules that signal to other parts of the body. If the gut bacteria change, the signals change too. “We’re really interested in seeing if we can manipulate the bacteria towards a healthier profile. Then the signals that they send up to the brain will also be healthier signals than if you have a bacterial community that’s distressed and imbalanced.”

It’s been well-established that having the ‘right’ gut bacteria is important for overall health and can reduce the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases. To encourage the right bacteria, you need to consume microbiota-friendly foods like dietary fibre. “One of the best fuels to feed the bacteria in our intestine is dietary fibre," says Reimer. "And all kinds of fibre are better than just focusing in on one kind." Dietary fibre helps maintain a diverse bacterial community made up of many different species that contribute important functions to the human body.

In her study of children with obesity, published in Gastroenterology, Reimer found that kids who consumed fibre in the form of a prebiotic supplement nearly doubled the amount of Bifidobacterium — one of the good bacteria in their intestinal tracts. Taking the supplement for several months also decreased the children’s body fat and level of blood triglycerides, a type of fat that can increase the risk of heart disease. In another study in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Reimer showed that taking a prebiotic fibre supplement can suppress appetite, a factor that can help manage weight.

While she used supplements in the studies, Reimer says people who are healthy can likely get all the fibre they need from food. And while you’re at the grocery store stocking up on fruit, vegetables, whole grains and nuts and other items loaded with fibre, she suggests picking up plenty of yogurt, sauerkraut and other fermented foods that contain probiotics — the good bacteria.

“But if you already have obesity, mild depression, or type 2 diabetes, then the doses of prebiotic and probiotics you get in foods may not be enough,” Reimer says. “It’s difficult to modify the disease course enough to really make a difference just with food. If we are looking to manage a disease, it's much more likely that you'll need supplements.” If you do take prebiotic and probiotic supplements, you need to take them every day in order to continue to make a difference and influence your gut microbiota. (Ask your doctor or pharmacist to recommend a good supplement or check this scientific source.)

As researchers learn more about how the bacteria in our gut affects the rest of our bodies, from producing more fat cells to sending signals to our brains, Reimer advises that we eat more fibre. “I preach that message all the time,” she says. “If you give the healthy bacteria the right food, you are setting yourself up for better overall health.”

Exploring brain connection with IBS

People who have gastro-intestinal (GI) disorders also experience higher rates of anxiety and depression, and those who have anxiety and depression are reported to have more GI symptoms. It’s thought that a better understanding of the gut-brain axis will help people with irritable bowel syndrome(IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and other chronic diseases. (Unlike IBD, IBS is a less serious disorder which causes no inflammation or damage to the bowel.)

“The gut and the brain could be connected in so many different ways,” says Dr. Remo Panaccione, MD, a professor in the Department of Medicine at the Cumming School of Medicine, director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinic and a renowned researcher in the field of IBD. “During different times of stress, does stress itself change the microbiome?”

This is one of the questions the IMAGINE study seeks to answer. The Canada-wide longitudinal study is looking at the role of diet and the gut-brain axis in IBS and IBD. “IBS is probably one of the most common digestive disorders in the western world,” says Panaccione.

Canada and Alberta have the highest reported rates anywhere. One in every 150 Canadians is diagnosed with IBD — and we don’t know why. “When we think about chronic disease in general, we see that there is a big difference in prevalence of disease depending on location,” says Raman. “For example, people in Africa and Asia tend to experience inflammatory bowel disease far less than we do in North America.”

But as these areas become more industrialized and their environments — and diets — change, we’re seeing higher rates all over the world, says Panaccione, who is a member of the CSM's Snyder Institute. Researchers are trying to find out why it's more prevalent in Alberta. “We think it’s probably a combination of the genetic pool here and something distinct within the environment,” he says. “Because not only do we see rates that are high in people who are born in Alberta, but we see people who move here develop inflammatory bowel disease.”

No one knows what causes IBD, which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Panaccione and dozens of other researchers in a total of 17 institutions across Canada are recruiting patients to explore the triggers that may cause the cramping, constipation and other painful symptoms associated with these disorders. “There’s a lot of interest in not only the diet, and how diet affects the microbiome but also how your psychological stressors work," says Panaccione. "How does the mind interact with the gut to cause symptoms? We know that both of those play a big role.”

The IMAGINE researchers will follow their patients’ diets, symptoms, stressors and microbiomes over many years by collecting stool, urine and blood samples, and having them fill out questionnaires about their psychological symptoms. “The hope is to better understand the key mechanisms in the diet-microbiome-host relationship,” says Panaccione. “It’s very exciting because we may find clues and predictably alter a person’s diet and microbiome or their gut-brain axis without using drugs.”

Feeding the health of people with IBD

Crohn's disease is a painful, debilitating type of IBD that causes inflammation of the digestive tract and tissues in the bowel. While various treatments can bring about relief or remission, there is no cure. People with Crohn’s suffer with abdominal pain, severe diarrhea, fatigue and malnutrition.

Raman and her colleagues have studied 100 people with Crohn’s for three years (and counting). The researchers have developed a diet that aims to reduce inflammation in the digestive tract and relieve the painful effects of the disease. “The anti-inflammatory diet was developed by correlating specific food items and nutrients to blood cytokines as well as stool inflammation,” she says. “We've shown that our diet improves all these inflammatory parameters in the setting of Crohn’s disease."

"There's an opportunity to use diet to improve inflammation in patients."

The anti-inflammatory diet has managed to alter people’s short-chain fatty acids (the nutrients created when bacteria eat sugar in the gut), an exciting finding with long-reaching implications. “Short-chain fatty acids are derivatives of the underlying gut microbiome," says Raman. "So the fact that we’ve been able to change the short-chain fatty acid profile suggests there's an opportunity to use diet to improve inflammation in patients."

In another ongoing study, Raman and her colleagues are looking at whether sulfur in the diet worsens the symptoms for people with ulcerative colitis (UC), a painful chronic disease of inflammation of the innermost layer of the intestinal wall. They’re studying how sulfur “mechanistically” induces inflammation and whether altering diet can help.

Sulfur occurs naturally in well water in rural communities across Alberta. And it shows up in a lot of processed foods like deli meats. But you’ll also find sulfur in a lot of so-called “healthy” foods at the grocery store. “Probably the highest level of sulfur comes from meats, particularly red meats, some chicken and other poultry,” says Raman. “Other sources would be cruciferous vegetables. Broccoli is a big source of sulfur, as are eggs and dried fruits like apricots, peaches and raisins.”

For many decades, researchers have been looking to genetics to find answers about chronic diseases. That emphasis is changing, Raman says, to include a larger examination into the person’s environment, and “diet and nutrition are a big piece of that environmental influence.”

Fettucine with fermentation

Fermentation is the process by which microorganisms, such as bacteria or yeast, break down a substance and change it into something else. With beer, wine and spirits, fermentation is what changes sugars into alcohol. In sourdough bread, yeast breaks down carbohydrates and gluten in the flour. And that’s why it’s long been known that sourdough bread is a healthier choice when you’re making a sandwich.

“Sourdough culture is a bacteria. That bacteria imparts a lot of beneficial impacts on the food and we've known this for generations,” says Dr. Jane Shearer, PhD, an associate professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology and the CSM's Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. “It produces different compounds. It alters vitamins. It breaks down the gluten a little bit. And so we know sourdough bread has a healthier metabolic profile for individuals.”

Now she’s working to see whether fermented pasta shows similar health benefits. Shearer and her colleagues are working with Kaslo Sourdough, a Kootenay-based sourdough pasta producer, to study whether their fermented product encourages lower blood-glucose responses, influences insulin levels and benefits the bacteria in the gut.

“The hypothesis is that the fermented product is the healthier choice,” says Shearer, who is a member of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute at the CSM. “If the digestion is changed and the glucose response is slower, then that might be a healthier choice, for example, for somebody who's concerned about blood glucose, which would be somebody with diabetes.”

In the year-long study, people came into the lab and some ate sourdough pasta and others ate conventional pasta. The researchers monitored their blood glucose responses after they ate. Initially the people had one serving a week and later in the study they ate pasta five days in a row.

“We haven't analyzed the data yet,” says Shearer. “But we're looking to see if you were consuming this pasta on a regular basis, compared to your conventional pasta, does it have an impact on the way you digest it, on your gut bugs, and how your body responds to it.”

Kaslo Sourdough makes their pasta based on an old recipe that’s been passed down in the family for generations. While the company keeps their recipe for fermented pasta secret, the benefits of eating fermented products is well known. “Over history, it's really been a game-changer,” says Shearer.

Another frontier for research

Dr. Silviu Grisaru, MD, an associate professor in the CSM's Department of Paediatrics, treats a lot of children with nephrotic syndrome, an autoimmune disorder that causes the kidneys to excrete too much protein in the urine. The child experiences swelling in the eyelids, feet, ankles and abdomen. If the disease isn’t treated, infections or thrombosis can develop, causing the child to have trouble breathing and eating. Treatment is effective but may cause serious side effects including weight gain, high blood pressure, swelling, mood swings, insomnia and fatigue.

“Patients just start pouring huge amounts of protein into their urine and they have to go on steroids for a number of weeks to induce a remission, but in many, the disease recurs once the steroids are stopped,” says Grisaru, a pediatric nephrologist at the Alberta Children’s Hospital and member of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute at the CSM. The majority of kids have multiple cycles of recurrence and remission until the disease never recurs while others experience ongoing relapses and progression to kidney failure.

Grisaru spends a lot of time talking to parents and explaining that doctors don’t know what causes their children’s disease. “All we are able to tell the parents is that it involves the immune system,” he says. “But we don’t really know what triggers it and the medications that we have to treat their children have serious adverse effects. Almost always at the end of the discussion, the parents ask ‘Maybe it’s something in the diet, maybe we could control the disease by eliminating or adding something to the diet?’”

And maybe it is.

Grisaru says doctors frequently hear stories from parents about how changing their children’s diet — removing dairy or gluten, for example — appears to help their children’s symptoms. “The literature is full of anecdotal case reports ascribing positive results to dietary changes, which are known to be associated with changes in gut microbiota,” he says. And he’s hopeful that as more and more research furthers our understanding about the role gut microbiota plays in our physical and mental health, researchers can start exploring possible connections between bacteria in the gut and children suffering with autoimmune diseases.

“I think the microbiome story is very promising,” he says. “There may be patients that, due to their genetic makeup, are susceptible to certain diet-related changes in their microbiome affecting their immune system. Or they may be susceptible to chemicals found in the environment or processed foods, affecting interactions between their immune systems and microbiome. Those are two leading theories explaining how diet may trigger autoimmune disease.”

Grisaru is exploring the feasibility for interventional controlled dietary trials in children with chronic autoimmune diseases in Calgary, hoping that a study may provide evidence needed to consider using diet to help his young patients. “There is a lot of interest from the parents to try to avoid side effects associated with conventional medications," he says. "In many, this motivation is strong enough to consider dietary interventions."

One day, Grisaru and other doctors who treat everything from autoimmune disease to depression may be able to help treat their patients with food. As researchers discover more about how the bacteria in our gut interact with the rest of the body — and affect our overall physical and mental health — the day may come soon when doctors start prescribing specific, personalized menus as medicine. Instead of stopping by the pharmacy, we'll head to the grocery store to pick up more yogurt and peruse the fresh produce aisle for the ingredients we need for better health.

– – – – –

Explore our programs

Participate in a research study

– – – – –

ABOUT OUR EXPERTS

Dr. Maitreyi Raman, MD, is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Medicine at the Cumming School of Medicine and medical director of the Alberta Centre of Excellence for Nutrition and Digestive Diseases. Her research is focused on nutrition support, including both enteral and parenteral nutrition. These research interests include investigating the effects of novel lipids on liver function in patients with parenteral nutrition induced liver disease, and assessing health outcomes of enteral nutrition in patients with advanced cirrhosis on the liver transplantation waiting list. See Maitreyi's publications on ResearchGate

Dr. Raylene Reimer, PhD, is a professor in UCalgary's Faculty of Kinesiology and the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology in the Cumming School of Medicine. She is also a member of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute at the CSM. Her research group's interests focus on understanding the full potential of nutrition to prevent and treat obesity and type 2 diabetes. Read more about Raylene

Dr. Remo Panaccione, MD, is a professor in the Department of Medicine at the Cumming School of Medicine and director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinic. He is also a member of the Snyder Institute for Chronic Diseases at the CSM. His special interest lies in the implementation and performance of clinical trials of new therapies in IBD. He also performs research in identifying new targets to develop new therapies in IBD. Read more about Remo

Dr. Jane Shearer, PhD, is an associate professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology and the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the Cumming School of Medicine. She is a member of the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute at the CSM. Her goal is to develop an interdisciplinary research program examining the interactions between nutrition, genes and the development of metabolic diseases including diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Read more about Jane

Dr. Silviu Grisaru, MD, is an associate professor in the Department of Paediatrics at the Cumming School of Medicine and a pediatric nephrologist at the Alberta Children’s Hospital as well as a member of the CSM’s Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. His research focuses on pediatric kidney disease and fetal renal morphologic abnormalities. See Silviu's publications on ResearchGate