.

Nov. 1, 2017

Universities have long been home to healthy debate and challenging ideas. Even so, people can be reluctant to discuss divisive topics like racism, sexual assault and gender issues, which can make it difficult to find common ground. In order to make progress, instructors whose courses question the status quo must first get students to feel comfortable examining and challenging their own beliefs and perceptions. We talk to a few UCalgary experts about how they tackle uncomfortable course material in their classrooms.

.

Dr. William Bridel, PhD, (WB) is an assistant professor at the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Kinesiology. His research explores socio-cultural aspects of the body, physical activity, and health. Read more about William

Dr. Michele Jacobsen, PhD, (MJ) is the associate dean (graduate programs) and a professor in UCalgary's Werklund School of Education. Michele's research program focuses on technology-enabled learning and teaching in both real-time and online Kindergarten to Grade 12 classrooms and post-secondary education using case study, action research and design-based research methodologies. Read more about Michele

Dr. Kiara Mikita, PhD, (KM) is the Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning's (TI) inaugural post-doctoral scholar working in the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL). Kiara facilitates the SoTL Foundations Program for Graduate Students and SoTL Foundations for Postdocs, facilitates and speaks in other TI workshops, and guest speaks and lectures elsewhere in the University and in the broader Calgary community. Her research interests include building community in the contexts of teaching and learning, examining and facilitating "safe spaces” in learning environments, and teaching about sensitive or controversial issues. Read more about Kiara

Dr. Yvonne Poitras Pratt, PhD, (YPP) is an assistant professor in UCalgary's Werklund School of Education. Yvonne is a Métis scholar whose family ancestry traces to the historic Red River Settlement and, more recently, to the Fishing Lake Métis Settlement in northeastern Alberta. Her research concentrates on the multiple ways in which transformative learning can be invoked within classrooms and at the community level through experiential learning and creative imaginings. Read more about Yvonne

WB: I teach courses related to sociological and cultural factors in sport and physical activity. So in my classes we discuss things like social norms, politics, ethics, body issues and sexuality in sport and in relation to the larger cultural context.

KM: My course was Sociology 401: Talk About Sexual Assault, which looks at the nuances of language and how it can shape perceptions of sexual assault.

YPP: I teach undergraduate and graduate courses on Indigenous education, as well as a Master of Education pathway called Indigenous Education: A Call to Action. We look at topics related to Indigenous issues, decolonization and reconciliation.

Sport can spark social change, but it can also perpetuate problematic norms.

WB: There are some “standard” topics that are covered in the intro class in particular. But I also draw on my own research and experiences for ideas. I was bullied at a young age for figure skating, and I came out early, so I've always had an interest in marginalized groups in sport. Ideas also come from current events in sport, like the Colin Kaepernick “controversy.” Sport can provide powerful messages and contribute to social change but sport also can reproduce problematic social norms. I try to get at both of these ideas through course content.

"Sport can provide powerful messages and contribute to social change, but can also reproduce problematic social norms."

MJ: Indigenous Education: A Call to Action was conceptualized about two years ago. I approached Yvonne to lead the design. I felt that our school needed to offer graduate education opportunities for teachers and school leaders to help them understand the recommendations and the calls to action coming out of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. To learn more about colonization and decolonization, what it means to talk about truth and reconciliation.

KM: I did my dissertation on how we talk about sexual violence. I interviewed sex crimes detectives, prosecutors, nurses, counselors, educators, and students about sexual violence. What they shared with me was that across the board, in all these practices that deal front-line with sexual assault, there’s no shared baseline training, which means no shared framework of understanding. The language is understandably different too, so in one sector someone is a complainant. In another, that someone is a client. In another, a survivor. My dream is to work with these groups to develop a shared learning program, which is why I love working at the Taylor Institute, because it is helping me explore that process.

YPP: In 2015, I was approached by Michelle to develop an Indigenous education graduate pathway. She gave me a lot of latitude as to how I wanted to vision or conceptualize that type of graduate education. And with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's work coming to the forefront and raising national awareness again, I thought what better way to bring reconciliation into the fray of education than to develop a graduate design based on responding to the 94 Calls to Action?

WB: I really try to get away from just lecturing. There's lots of discussion and I make use of both academic articles as well as more “mainstream” texts, such as TedTalks and relevant news articles and opinion pieces. I try to incorporate other peoples' stories as much as possible in effort to expose students to experiences they might not know about. I give them quite a bit of freedom in the way they complete their assignments so that they can focus on issues that are meaningful to them. I bring in guest speakers who can share their experiences and knowledge with the students and I try to incorporate creative group projects in each course I teach. I use ongoing research to inform courses as well, to ensure we can have good conversations about issues with contemporary examples.

KM: The Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning offers a course design program, so I took that. It's literally walking through designing an entire course. I had so many ideas that I was probably going to deliver in a pretty straightforward and relatively unexciting way, because that’s what we’re used to. If it wasn't for course design, I don't know what the learning in my course would have looked like. I think it was instrumental in facilitating the positive learning experiences that students had.

"I use humor and storytelling to inject the joy back into learning."

YPP: As a Métis person it was really important to me to have a collective approach to the program design. I gathered together a group of trusted colleagues, and it was a mix of indigenous and non-indigenous people, and we talked about what a four-course pathway would look like that responded to the calls for action in the educational realm. We deliberately included a service learning project at the end, so the students wouldn't be only learning theory. We also intentionally infuse aesthetics. The students are involved in Métissage projects, where they have to weave Indigenous and non-Indigenous perspectives into some really creative imaginings around reconciliation. We deliberately use the arts as an avenue of expression, and I also use humor and storytelling to inject the joy back into learning. When you're mired in learning the oppressive history that surrounds our peoples, you can get really stuck. So I do my best to infuse hope into the courses, too.

The language around sexual assault can be nuanced and complicated.

WB: A lot of what we do involves challenging popular views of sport, which tend to be positive. Traditionally, sport is viewed as being inclusive, where everyone gets an opportunity to play on a so-called level playing field, as beneficial to society, as healthy, as good for you in terms of building skills like teamwork, time management, work ethic. That's not always the case; people can be limited in access to sporting spaces or alienated and marginalized in sport if they have been able to join a team or league. Sometimes there's resistance to accepting different points of view when we talk about things like LGBTQI2S issues, obesity and social responsibility, race, or gender issues.

MJ: Decolonization is disrupting commonly held assumptions about power and relationships, disrupting commonly held understandings of land ownership, of land use, of cultural protocols. It's helping people become aware of history, not just from the colonizers' perspective, but from those who were colonized, understanding concepts of privilege and who's privileged, who isn't, who has power, who doesn't, who's benefiting from the current organizational structures and who isn't. Being aware of additional barriers that people who are colonized face is a part of decolonization. It can be challenging to face some of your own ignorance or to face some of your own beliefs and realizing, you don't know, "I didn't realize that I grew up with this gap in my understanding. I didn't realize I was part of the problem. I have this commitment to whatever standards or equality, or I had this idea that we all experienced these things equally, now I'm realizing, no we haven't." That can be really hard for people. It can make them feel regret and guilt and shame.

"It can be challenging to face some of your own ignorance or to face some of your own beliefs."

KM: In teaching about sexual violence, student welfare is always potentially at stake. Because this is a self-selected course, I can’t know what's drawing people into this course. If people are going to talk about something as sensitive as sexual assault, they need to feel as comfortable as possible in that learning environment. We could have had a wildcard who was really vocal, on a totally different page than the others, who could have destabilized and fractured the safety that we built. But I think that by actively building classroom community, we can mitigate these kinds of challenges.

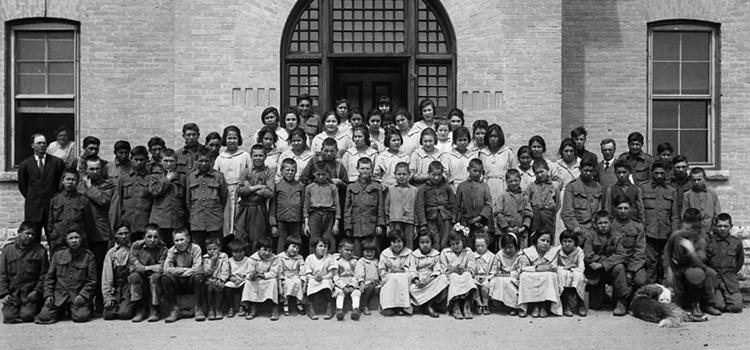

YPP: We're talking about really difficult stuff that occurs at a political level. We're talking about sexual abuse, we're talking about systemic oppression. The discrimination or racism against Aboriginal people is something that is sadly socially sanctioned here in Canada. We tend to be tolerant and polite around other groups, including newcomers, but with Indigenous people even the best, most well-intentioned Canadian will often be racist without giving it a second thought. Routinely, in my undergraduate course, I have a good portion of the class disclosing that they were or are racist toward Aboriginal people, knowing full well that I am Métis. So, we're having to bring a lot of difficult learning to the forefront. We've got people sharing stories about residential school experiences, who either have family members or who were themselves in residential schools. There's often a lot of emotional turmoil as people understand that Canada is not what they think it is. We're tearing up fundamental beliefs about who we are as a nation and who we are as Canadian citizens.

Challenging people's views of history can cause tension.

WB: Because I'm teaching potentially uncomfortable material, I feel that it's up to me to create an environment where students feel open to discussing different points of view and challenging what they believe. I do that through humour, through being open to sharing my own experiences, and ensuring that conversations are also rooted in the course materials we’ve engaged with – that’s the common element that all students share. I also have to be willing to accept feedback that I don't necessarily like! For example, when I first started teaching, just after I finished my PhD, I got feedback that I was inadvertently alienating some students through my approach – which was arguably a bit “in your face.” I realized that if I was excluding certain students through my approach, then I wasn't fulfilling my responsibility as a professor. I learned an awful lot in my first year of teaching and try to continually grow in that regard so that students can be exposed to and gain new knowledge, or simply reaffirm it.

KM: Lots of ice-breakers. They sound cheesy, but they work. For example, we did syllabus speed dating, where the students would sit in small groups and answer silly, low-stakes questions that I had prepared for them. Then I'd have them find something in the syllabus together. Then they'd move onto the next series of silly and syllabus related questions. The next day we would do a different exercise. I also moved back and forth between assigning groups and having students choose their own groups, depending on the nature of the material in focus. By the end, they seemed to be a community. They were comfortable with each other.

Another time, before we did class presentations, I had everyone come up and read really awkward tongue twisters in front of the class. Everybody screws up tongue twisters, so there's no cost to it. You get to make an ass of yourself like the rest of us and sit back down. As students walked up to read their tongue twister, and as they left, the rest of the class cheered for them. It helps create that space where it's okay to speak in front of each other, and where we get to practice being supportive audience members.

"You get to make an ass of yourself like the rest of us and sit back down."

YPP: I'm well aware that the term "decolonizing" sets non-Indigenous people on edge right away. So while I'm very sensitive to the fact that the Indigenous perspective is foregrounded, I also have to consider the non-Indigenous students, and how they are positioned. The students that sign up for our “Call to Action” pathway program are very intentionally setting themselves up to be uncomfortable, if not provoked by dark truths about our country. So I'm very sensitive to the fact that I have to create a space that is safe enough for them to stay, to keep up the work, and to be inspired enough to respond to the Calls to Action.

There are times where you have to be quite vulnerable in order to have people open up to alternative histories. I've experienced the negative impacts of a colonial past and so when I teach I draw from that lived experience. So I'm exposing myself to the students, but I'm also placing a lot of trust in them to at least be respectful of what we've gone through as the First Peoples of Canada. I ask students to ask questions of me “they wouldn’t ask out loud.” They're anonymous, and every day that I teach I commit to answering at least one of them.

And we do things like we jig. I'm Métis, so on the final day, understanding that we've gone through a really rough term together, I'll put on the Red River Jig and we get up and dance. They need to have joy, and hope, put back into them.

KM: The course design instructors suggested that I let the students express their learning in any way they wanted to for their final assignment. To ensure fairness, we constructed the grading rubric together. The results were breathtaking. They did a graphic novel, moving and hilarious videos, a cocktail recipe, a spoken word piece, a magazine article. It was so far beyond anything I could have dreamt. I think it was this sort of meaningful learning – that they were in charge of deciding how to express – that made this course transformative for all of us.

YPP: During the program, we try to open students up to alternative ideas. We inspire through stories. We take them to the Glenbow Museum. We spend a day out on the Siksika reserve. We tour a residential school. We do ceremonies. We do the Red Dress Project around campus. But I always give them the option and say to them, "We can do this or not. It's up to you guys." I try to share the power with them. It's very much a leveling of the power and that's very intentionally done. So, it's not me up front saying, "Call me Dr. Pratt." It's saying "let's learn how to do this together."

Conversation is key to overcoming social challenges.

WB: The Millenial generation is often criticized for supposedly being entitled and self-centred. But in my experience, I just don’t see an entire generation that way. I see young people who are compassionate and empathetic, who want to be encouraged to think critically, and who are committed to social change. I try to acknowledge that, to encourage that, and to give them the tools they need. One of the challenges of teaching and engaging in critical thinking is that we can tend to focus mostly on the negative, or the things that still need to change. Of course, this is super important. But it’s also important to talk about what has changed, what aspects of sport for example, have shifted to become more inclusive in some way. To talk about activists and allies who have been brave in their roles and made a difference.

MJ: The graduate pathway involves a service learning project, which students determine for themselves. It might be a problem-based project, a school division project, something in a community organization, it may be something that happens on reserve. Each student is supported in identifying what they want to do and then in carrying it out. The program increases their awareness and knowledge so that they can bring those insights into the communities that they work with. They are taking action with their community-based project, so we know they're having local impact.

"It's very important to me to teach a dark subject with light."

KM: It's very important to me to teach a dark subject with light. The first time I taught my course, there were a number of relevant things happening in the media and on the Internet. Jian Ghomeshi, Brock Turner, Kesha. So instead of analyzing only academic articles, we took them up in light of tweets and funny social justice videos, like Megan MacKay's makeup tutorials. We took up intellectual material in a way that was relevant to them, so that it spoke their language, and they could explore that in a way that resonated with them and was hopeful. There is so much hope in this work, and I wanted them to find it and feel it, because they can do things with that.

YPP: The graduate program students are practising professionals. They're leaders in their careers, and as a result, they are potential change agents. If we can inspire power holders to respond to the calls to action, that's where you're going to get structural change. So the program was thoughtfully and carefully designed to think about how do we actually sway people? How do we open up this kind of conversation? We know that racism is one of the underlying currents in Canadian society, that people shy away from or only share amongst their inner circle. With this program, we're having people step up and say, "You know what? I want to take this work up in a meaningful way."

Participate in a research study