.

June 1, 2018

Researchers often seek to make sense of the unknown, to explain the unexplainable, to bridge chasms in our understanding of the universe. But it can be just as important to challenge and validate what we think we already know. "It's surprising how much research you have to do to prove the obvious," says Dr. Jeff Caird, PhD, a professor in the Department of Psychology in UCalgary's Faculty of Arts.

In this case, "the obvious" is that driving while impaired by cannabis is a bad idea.

As part of legalizing cannabis, Canada has had to create laws to deal with driving while impaired by cannabis. "It's very clear that the use of cannabis before driving is an issue," says Caird, whose labs focus on reducing the number of injuries and deaths in transportation and health care. "The issue has been somewhat explored by Health Canada and Transport Canada leading up to legalization, but there are still a lot of things we don't know."

Part of the difficulty with cannabis and impaired driving is that so few studies have been done to date. "It's hard to get access to cannabis for scientific use," says Sarah Simmons, a PhD student supervised by Caird in his Cognitive Ergonomics Research Laboratory. "So the level of research activity has been sporadic."

Simmons is working on a meta-analysis, compiling the statistical results of experimental studies in order to summarize the available evidence. In the studies she's looking at, conducted in driving simulators or on the road, scientists tested drivers who had taken cannabis and those who hadn't and compared the results. They measured things like hazard detection and response, vehicular control, lane keeping, and ability to maintain speed and headway.

One of Simmons' preliminary insights is that unlike with alcohol-impaired drivers, drivers impaired by cannabis seem to have an awareness that their driving is affected. "Some studies show that they slow down and they increase their headway in an attempt to compensate," she says. "Whereas with alcohol, people underestimate their own impairment."

However, Caird says some people – especially young males – think their driving is safer when under the influence of cannabis. In response, he's planning a study to determine why that belief is so persistent and how to counteract it. "Because they think they're better drivers, they drive," he says. "Why don't they understand that it's impairing? How do we change their intentions to drive?"

While the risks associated with drivers who are impaired by alcohol and those impaired by cannabis are different, both are still much more likely to be involved in a crash than sober drivers. "Alcohol makes people much slower to respond to their surroundings, such as when pedestrians walk into the street or cars pull out," says Caird. "With cannabis, they're also slower. That's one of the main reasons why both groups crash – they don't respond fast enough to immediate threats."

If experiences in other jurisdictions are any indication, legalizing cannabis will make it easier for researchers to study its effects and to determine what changes, if any, legalized cannabis is causing.

"One unintended consequence is that if people consume cannabis, they're less likely to consume alcohol," says Caird. "One of the declines you see in Colorado after legalization is in the consumption of beer. Maybe that means people are less likely to drink and drive, which is the number one killer of people on the road. The more you drink, the higher the risk of a crash. We don't have the numbers to support this yet, but anything that reduces drinking and driving is going to reduce fatalities."

With her meta-analysis, Simmons also intends to figure out where the gaps are in the existing research. "There's going to be much more research on cannabis and driving in the future," she says. "One of my goals is to identify limitations and problems, so scientists have something to refer to. What they should be looking for, what biases they should avoid, how many participants to recruit, and so on. We need better research going forward."

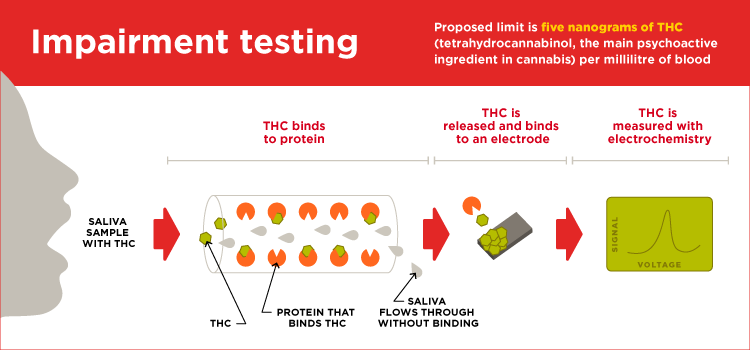

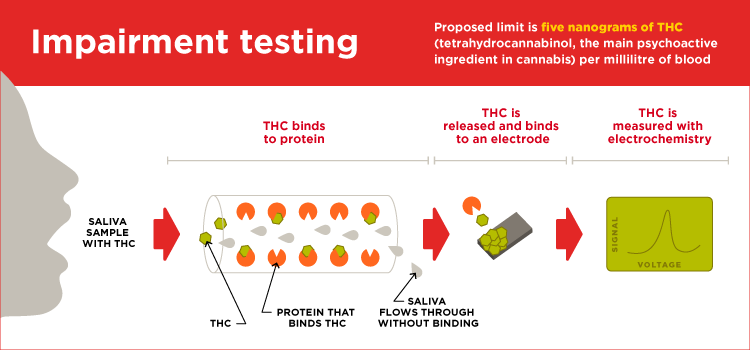

Like with alcohol, the legislation for impaired driving with cannabis includes a limit on how much THC (tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive ingredient in cannabis) can be in your blood before you get charged with impaired driving. Presently, the limit is five nanograms per millilitre of blood.

The issues with such a limit are that there is currently no device like a breathalyzer that police can use to screen for impairment during roadside stops, and there's debate over whether or not five nanograms of THC per millilitre is an accurate indicator of impairment.

While alcohol diffuses throughout your blood and bodily tissues fairly equally and predictably, THC does not. Everyone responds differently to THC and unlike alcohol, there are vast differences in types, strains and sources of cannabis – and in its THC content. THC is also fat-soluble, meaning your body stores it in its fat cells, where it can be released days or weeks later. The metabolized THC is still detectable by blood tests, even though it's no longer psychoactive.

"We've been living with alcohol for a very long time as a society," says Lisa Silver, a former criminal lawyer and an instructor in UCalgary's Faculty of Law. "And most of us can kind of self-regulate. We kind of know what 0.08 blood alcohol content feels like. And we can calculate the elimination rate based on our weight and the amount of alcohol consumed. But what's the elimination rate for THC? The evidence says it can stay in your blood for days."

"Is the cannabis we're buying going to be properly labeled with THC content?" asks Silver. "How am I going to know how strong it is? It's easy to say 'don't smoke and drive,' but for how long? If I have a glass of wine on Monday, I wouldn't assume that I shouldn't be driving on Wednesday."

Silver says elimination rates will be even more controversial with new impaired driving laws. New legislation makes it illegal to be impaired not just while driving, but within two hours of driving.

Currently, prosecutors must prove you were impaired while you were operating a motor vehicle, which they can do with alcohol by using the standard elimination rate to calculate backwards from the time you gave a blood sample to the time you were suspected of driving while impaired. But since THC affects people differently than alcohol, extrapolating time of impairment backward is much more difficult.

"The way the act reads now, it says 'everyone commits an offence who operates a motor vehicle while the person's ability to operate the vehicle is impaired,'" says Silver. "According to the new act, it will be, 'everyone commits an offence who is impaired within two hours after ceasing to operate a motor vehicle.'"

In theory, police could show up at your door up to two hours after you stopped driving and, if they find you impaired, charge you with a crime. Silver says the new provisions are intended to eliminate so-called "bolus consumption," where people who are pulled over consume alcohol in front of police in order to skew test results and be able to claim they weren't intoxicated while driving.

Part of the rationale for legalization is to ease the burden on the court system and to stop saddling people with criminal records for what are perceived to be minor infractions. But Silver predicts the new legislation will continue to clog up the courts and result in criminal charges, but for different reasons. "Our laws need not be overbroad, and this is overbroad," she says. "We need our laws to fit the circumstances properly."

Whether or not the five-nanogram-per-millilitre limit for THC content in the blood is an accurate measurement of impairment, another problem is that police have no reliable way to screen for THC during roadside stops. They rely on a combination of intuition and so-called drug recognition experts to determine whether someone they pull over is impaired and should undergo a blood test.

"There are ways of measuring THC in blood and saliva, but none of them are portable or could be used for roadside tests," says Dr. Justin MacCallum, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry in UCalgary's Faculty of Science. "You take a sample and send it off to a lab, and two weeks later you get results. We're more interested in a screening tool like a breathalyzer. Something police can use to say, 'okay, this is someone we need to take down to the station.'"

To address the issue, MacCallum and Dr. Viola Birss, PhD, a professor in the Department of Chemistry, are working together to develop a small, simple device police can use to detect the presence of THC in someone's saliva. "The problem is that THC isn't volatile, so it isn't in your breath," says Birss. "You have to find it in bodily fluids." Having the police take blood samples roadside is obviously not feasible and could get into rights violations, so saliva is the next best thing.

But it's not as easy as it sounds. Of the hundreds of cannabinoids that show up in blood and saliva tests, only a few of them, like THC, are psychoactive. The rest, like cannabidiol, which is the medicinal compound in medical marijuana, don't cause you to be impaired. Also, for chronic users, once the body metabolizes THC, it's no longer psychoactive but can still be detectable for weeks.

"All of these compounds are fat-soluble, so they end up in your fatty tissue and get slowly secreted out of your body," says MacCallum. "So imagine someone is a chronic marijuana user who stops cold turkey, and two weeks later they go for a jog and release a bunch of these fatty molecules into their bloodstream. They would test positive on a crude screening test, but that doesn't mean they're impaired."

A further wrinkle is that any roadside sensor would have to be extremely sensitive to detect five nanograms of anything. To put it in perspective, five nanograms amounts to about one ten-thousandth of a grain of salt.

In order to solve their two main challenges – how to separate psychoactive cannabinoids from non-psychoactive ones, and then how to count them – Birss and MacCallum are relying on biomolecular engineering and electrochemistry.

"My lab is taking a protein that binds naturally to THC and some of these other compounds, and engineering it to make it more specific to the things we care about," says MacCallum. "We can use this protein to fish out the molecules that make people high, and then use electrochemistry to measure them."

.

"THC can be oxidized to create an electrical current," says Birss. "The more THC present in the sample, the bigger the current."

The protein that binds to THC in the body is called Fatty Acid Binding Protein (FABP). Its job is to shuttle certain molecules around your brain. One is an endocannabinoid – a cannabinoid your body produces on its own – called anandamide. THC binds to the same molecule. In theory, the FABP could be used to separate psychoactive cannabinoids from benign ones.

The challenge is that the difference in the molecular structures of those cannabinoids is minute – often simply a matter of one or two more atoms of oxygen. "Here you have this molecule, and the only thing that's different from the next molecule is this one tiny little part over here," says MacCallum. "You have to design the protein so that the molecule you're interested in fits, and the other ones don't."

Looking beyond cannabis, MacCallum and Birss imagine being able to detect the presence of virtually any drug during a roadside stop. "There are perhaps way more impaired drivers than we would like to contemplate out there," says MacCallum. "There's a whole spectrum of other things that need to be detected."

"People are taking all kinds of drugs and medications that impair their ability to react quickly," says Birss. "There's a bigger problem than we all realize. That's the next horizon."

Jeff Caird has what may seem like an obvious solution. "For people who choose to use cannabis and consider driving – don't."

– – – – –

– – – – –

Dr. Jeff Caird, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Psychology in UCalgary's Faculty of Arts. His research focuses on human factors in health and transportation, aging, patient safety and traffic safety. Read more about Jeff

Sarah Simmons is a PhD candidate who works with Jeff Caird in the Cognitive Ergonomics Research Laboratory. Her research interest are human factors in health and transportation and traffic safety.

Lisa Silver is a former criminal lawyer and an instructor in UCalgary's Faculty of Law. As a research lawyer, Lisa has written numerous facta and opinion briefs for matters before all levels of the Alberta courts, including SCC leave applications. Read more about Lisa

Dr. Justin MacCallum, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry in UCalgary's Faculty of Science. His lab studies protein structure and biomolecular recognition using a combination of computational modeling and biophysical experiments. Read more about Justin

Dr. Viola Birss, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Chemistry in the Faculty of Science. Viola is a world leader in the area of electrochemistry at surfaces and interfaces and in nanomaterials development for a wide range of clean energy applications. Read more about Viola