The portrayals in "Heather Has Two Mommies" have changed with each edition.

Feb. 1, 2019

In the opening pages of Joshua Whitehead’s novel, Jonny Appleseed, the young Two-Spirit protagonist describes watching Queer as Folk on his kokum’s (grandmother’s) TV: “I loved QAF; I wanted to be one of those gay men living their fabulous lives in Pittsburgh … I wanted to be sexy and rich.”

Jonny goes on to talk about It Gets Better, the social media campaign launched in 2010 to empower and encourage LGBTQ youth: “They told me that they knew what I was going through, that they knew me. How so, I thought? You don’t know me. You know lattes and condominiums — you don’t know what it’s like being a brown gay boy on the rez.”

These two moments are revealing in a metafictional way. Inside a book that invites Indigenous youths to recognize themselves in a queer narrative is an Indigenous youth trying to recognize himself in a queer narrative. But that fictional act of recognition is a struggle.

Why is this self-recognition important? Marginalized groups are often underrepresented (or completely ignored) in art and media, for reasons of gender identity, race, sexual orientation or social status — a concept called "symbolic annihilation." This lack of representation makes marginalization worse, as it reinforces traditional social and cultural norms by pretending other identities don't exist or don't matter.

So when people who fall outside traditional norms see themselves reflected in art and media — especially in a positive way — it goes a long way toward empowerment and overcoming discrimination.

The past few decades have seen enormous transformations in how our culture understands gender — and those shifting perceptions are beginning to play themselves out in popular culture and media.

A quick surf through Netflix shows that the male/female binary is loosening and broadening. Casts increasingly include characters who are gay, bisexual, trans or simply not conforming to traditional gender norms.

There is Kalinda, the bisexual investigator in The Good Wife. Or RuPaul and his Drag Race, a celebration of all things queer. Or Sophia, the transgender prisoner in Orange is the New Black, played by Laverne Cox, who is a transgender woman.

But as the narrator in Jonny Appleseed suggests, queerness is different for everyone. It intersects with race, economics, gender and more. So while it's encouraging to see more diverse characters portrayed on the screen and page, it would be naïve to suggest that the Netflix buffet of queer-friendly programming solves all gender discrimination problems.

So what role can artistic representations play in a shift toward embracing more inclusive notions of gender? Can art not only reflect a more positive vision of gender-nonconforming people, but also effect change in how gender is perceived?

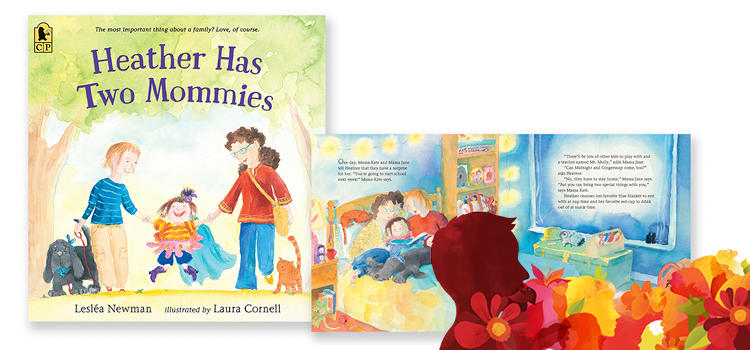

Derritt Mason, assistant professor of English in UCalgary's Faculty of Arts, studies gender and sexuality in children’s and young adult literature. In a soon-to-be published book, he explores the evolution of queer characters in literature and media for young people. His reading list includes a picture book, called Heather Has Two Mommies, by Lesléa Newman — one of the earliest children’s stories about lesbian relationships. It’s the story of Momma Jane and Momma Kate, who become a couple and have a child together.

The portrayals in "Heather Has Two Mommies" have changed with each edition.

The evolution of this book provides insight into changing cultural norms around gender. What’s interesting about Heather, says Mason, is the way the book changes over time, from its original version in 1989 to its tenth and twenty-fifth anniversary editions, reflecting shifting views on gender and sexuality.

In the original text, about a third of the story is devoted to the mothers’ relationship and the pregnancy. “It’s pretty detailed,” he says. “We hear about everything from artificial insemination to sore breasts.” But the tenth anniversary edition omits those details entirely, and "the 2015 edition,” says Mason, “nearly omits the mothers altogether, and changes how it represents Heather.”

This is the direction queer picture books are going.

Whereas Heather had been portrayed as somewhat of a tomboy in early editions, she now becomes more ambiguous and gender non-normative. She wears cowboy boots and a tutu, and her toys range from stuffies to tools. “This is the direction queer picture books are going,” says Mason. “Not so much explaining what gay adults are like, but showing the queerness of a child.”

This shift reflects social and cultural changes in the gay, lesbian and queer civil rights movement. “I’d like to think that we're beginning to see more acceptance of gender queerness, and children given greater free rein over their gender creativity,” says Mason.

Mason’s analysis of books like Heather Has Two Mommies reveals the dualistic role of literature: it can act as both mirror and window. This metaphor, born in a 1990 article by Rudine Sims Bishop, titled “Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Glass Doors”, is useful, especially in tracing the shifting portrayals of queerness in literature. “The metaphor suggests that when you read a book, it should reflect yourself back to you, but it should also show you something about the outside world,” says Mason.

Early stories for children and youth were more window-like than they are now, and some were didactic, teaching readers about what it meant to be gay. “In the 80s and 90s, these books were really important,” says Mason. “They were written for young people who had queer family members, as a way of explaining how being a gay adult works.”

Windows on gay life were not well accepted in the 90s, though. Heather Has Two Mommies was challenged 42 times by American legislators and parents, in attempts to remove it from libraries and schools. Soon after the book was published, New York City Schools Chancellor Joseph Fernandez added it to a queer-friendly, first-grade curriculum resource called Children of the Rainbow, which encouraged acceptance for cultural and sexual diversity.

The "Children of the Rainbow" initiative encouraged acceptance for cultural and sexual diversity.

Although the Rainbow project contained no lesson materials about homosexuality, other than a suggestion that teachers should inform students that some people are gay and deserve respect, it sparked outrage. Citing passages from Heather Has Two Mommies, one New York school district president called the curriculum guide “dangerously misleading lesbian/homosexual propaganda.” Fernandez received death threats and ultimately lost his job.

Now, some 25 years later, Heather Has Two Mommies is considered iconic. It shows the ability of literature to act as a mirror for those eager to see themselves in literature. Says Mason, “It exemplifies contemporary books that actually reflect queerness back at young people, which is good.”

According to Mason, the evolution of young people’s queer literature has been a gradual process. Heather Has Two Mommies owes its iconic status to a long history of gay rights activism. One of the most significant watershed moments for queer children’s literature happened in 1969, when activists demonstrated against police, protesting raids on queer spaces and persecution of queer people in general.

The protest happened at the Stonewall Inn — a gathering place for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people in New York City’s Greenwich Village. The Stonewall Uprising is now known as the birthplace of the gay rights movement. “This is when we start to see an early shift in queer literature,” says Mason.

The year 1969 saw the publication of I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip, by John Donovan. “This was the first queer young-adult novel, notable for its candid depiction of a relationship between two teenage boys,” says Mason. “After Donovan published this book, readers started calling for more of the same, since there was so little of it available.” After Stonewall, queer literature for children began to make a public entrance.

But queerness wasn't invented in 1969. So where were the queer characters prior to Stonewall? “Back then, in children’s literature,” says Mason, “queerness was a ghostly presence in the story; there was no character who said, ‘I’m gay,’ or, ‘I’m a lesbian.’” If this was a mirror for queer readers, it was an antique that didn't reflect clearly: the spectre of queerness was present in the text, but you had to look hard to see it.

Mason says there is a way of producing queerness in a text through one’s own interpretation. “And of course this existed long before Stonewall,” notes Mason. “It’s what people had to do to see themselves reflected in texts where they weren’t otherwise represented.”

In this world of antique mirrors, a reader could watch The Wizard of Oz, for example, and find homoeroticism in the relationship between the Tin Man and the Scarecrow. “This is now hailed as a classic gay or queer text,” says Mason. “‘Friends of Dorothy’ used to be code for ‘gay man,' back before Stonewall.”

In some ways the portrayal of queerness has come full circle in children’s and young people’s literature. “We’re now seeing more ambiguity where gender and sexuality are concerned,” says Mason. “Not a return to the closet, but a return to a queerness that is more slippery than a definite form of gay or lesbian identity. And this ambiguity reflects what’s going on out there as we redefine gender and sexuality.”

This ambiguity reflects what’s going on out there as we redefine gender and sexuality.

This is what theorizing queerness invites readers to consider. “Queer theory,” says Mason, “suggests that the categories of man and woman are not inherently natural or biological. The way you’re biologically sexed doesn't necessarily determine your gender, which doesn't necessarily determine your sexual desire. So now we’re seeing much more fluidity around gender and sexuality.”

UCalgary graduate student Joshua Whitehead combines theory and narrative to explore the fluidity of gender and sexuality. Whitehead is an Oji-Cree, or nehiyaw, Two-Spirit writer, completing a doctoral degree in English.

In his novel, Jonny Appleseed, Whitehead takes philosophical concepts — from psychoanalytic theory to queer and feminist theory — and weaves them into his writing, resulting in a story that balances the creative and the academic without becoming mired in jargon. “I want my work to be accessible to my mother and my grandmother,” says Whitehead. “Like dinner conversation.”

I’ve been trained to think about the English canon, and to write ‘white.’

For Whitehead, writing in an academic setting has its challenges. “I’ve been trained to think about the English canon, and to write ‘white.’ So I’ve been trying to think outside of that.” He also resists the idea that scholarly work can only be passive, critical observation. “Academia likes to theorize rather than actively engage within communities or perform radical work,” says Whitehead. “I’m trying to do both.”

He is gaining substantial recognition for his creative work. Jonny Appleseed was short-listed for the Governor General’s Literary Award and long-listed for the Giller Prize. The novel tells the story of Jonny, a meditative cybersex worker who calls himself "an NDN glitter princess." ("NDN" is a shorthand term for "Indian," used by some Indigenous people to refer to themselves.) Now living in Winnipeg, he must return home to the rez (reserve) for his stepfather’s funeral. It’s a homecoming complicated by the way friends and family feel about Jonny’s Two-Spirit identity.

The term “Two Spirit” was coined in 1990 in Winnipeg. “It’s a pan-Indigenous term,” says Whitehead. “There are more than 150 different iterations across Turtle Island, or North America, from different nationhoods that have terms for Two Spirit in their own languages. For example, the Ojibwe Algonquin peoples, where I’m from, have the term niizh manidoowag.”

Two Spirit, which refers to having both the male and female spirit within, is a phrase that’s often equated with LGBTQ. But the two terms are different. “Two Spirit isn’t just about sexual identity or sexual preference,” says Whitehead. “It also encapsulates things like gender — but gender steeped in tradition and ceremony.”

Two Spirit isn’t just about sexual identity or sexual preference.

In the Cree and Ojibwe cultures, for example, labour has traditionally been gendered, with men taking on roles like hunters and women being the caretakers. “But we also had a third space occupied by Two-Spirit people,” says Whitehead, “where women are inclined to do the work of men, and men are inclined to do the work of women.” This space is fluid, even though it appears to be binary at first glance. “It wasn’t just A or B,” says Whitehead. “It was A to Z, and there was all this space in between.”

Whitehead feels he has a complicated relationship with the Two Spirit term. “It calls me home,” he says, “giving me Indigenous sovereignty as a queer Indigenous person. But Two Spirit is also a fraught term right now, because Indigenous Peoples don’t always bring Two-Spirit people with them when they try to heal themselves.”

Queerness is sometimes demonized on the reservation, according to Whitehead. “You can find the extreme binaries of gender there, since we have some traditions that are neo-colonial.” The reservation can be precarious — even deadly — for Two-Spirit people. “The idea of being queer is scary,” says Whitehead. “That’s why we see queer people leaving the reservation and seeking queer utopias, like Toronto, Vancouver or San Francisco.”

Because the concept of Two Spirit is so bound up with precariousness, Whitehead prefers to use the term Indigiqueer. “It “explains how we as Indigenous and queer peoples are both simultaneously,” says Whitehead. “We don’t have to obliterate one to be the other. And that attitude seems to be on the rise right now.”

Whitehead hopes his research and writing can lead to understanding and acceptance of Two- Spirit Peoples. Like Derritt Mason, he believes in the need to see yourself depicted in narratives, in order to know yourself. But how Indigenous Peoples are depicted matters deeply. “If you watch a film with Indigenous Peoples in it, they’re usually alcoholic or addicted to substances, or dying,” says Whitehead. “So what does it mean to see yourself in these mirrors that tell you, ‘your life is a trajectory of alcoholism or substance abuse?’”

I want them to see themselves as capable and powerful and healthy.

Whitehead sees himself not just as a writer, but a mirror-maker. “My main goal is to craft those mirrors for kids to see themselves in. I want them to see themselves as capable and powerful and healthy. Because if a boy from a rez housing project can be sitting in the University of Calgary in a doctoral program, so can you. That’s my whole goal.”

Media representation can be a source of power for marginalized communities.

If Joshua Whitehead sees his work as a sort of mirror, inspiring new perceptions of identity, the work of Dr. Laura Hynes, DMA, might be described as a springboard to social progress. Hynes is an assistant professor of voice in UCalgary’s School of Creative and Performing Arts. Her research often focuses on social-justice issues, and one of her current projects, funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council grant, explores transgender voice transition.

Hynes met singer Dr. Ari Agha when they signed up for singing lessons with Hynes. Agha, who has a PhD in sociology and conducts public policy and program evaluation research for The City of Calgary, wanted to hone their vocal skills for performances with choirs. “I shared with Laura that I had been thinking about taking testosterone as part of my gender transition,” says Agha. “That’s how our project got started.”

The effects of testosterone on the singing voice are still a mystery to those contemplating transitioning. “We just don’t have much research into what happens to an adult’s singing voice on testosterone therapy,” says Hynes.

So far, research on testosterone therapy has only examined its effects on the speaking voice. “They’ve looked at how much the voice drops,” says Agha. “And how quickly. And they’re asking whether trans people are satisfied with their voices afterward.” The answer to that question is that satisfaction varies dramatically. “Not everyone is happy with their voice afterwards,” says Agha.

To create a benchmark for vocal progression, Agha records the same song — “Simple Gifts” — every six to eight weeks. Hynes and Agha have also recorded each of Agha’s weekly singing lessons for the past two years.

Hynes makes observations about Agha’s range, transition points, and timbre. They also record how much testosterone is in Agha’s bloodstream.

Together, Hynes and Agha are documenting how Agha’s voice changes as Agha takes testosterone through the transition process. Hynes and Agha see this research project as a case study that will offer useful information to other singers considering testosterone therapy.

It can be unsafe to be perceived as something other than a man or a woman.

“We know that in assigned male adolescents, testosterone makes the larynx and vocal chords grow in size and mass, and the voice becomes deeper,” says Hynes. “But for an adult taking testosterone, it’s a different process.” The cartilage in the larynx is already fully grown, so that raises questions about the effects of testosterone on the adult voice. “What happens when the vocal chords need to grow and the larynx and vocal tract may not grow in tandem?” says Hynes. “How does that change the outcomes for a singing voice?”

The other key difference between adolescent and adult voice changes has to do with speed. “A lot of folks want to get through the gender transition process as quickly as possible,” says Agha. “Those who identify as men want to be perceived as men — yesterday.” But Agha also says that there are security reasons for moving at top speed. “It can be unsafe to be perceived as something other than a man or a woman. If people aren’t sure which you are, it’s not a good place to be."

So the stakes are high. Even when people are dedicated singers, they are willing to make sacrifices as they transition. “I was willing to risk losing my voice because of the testosterone therapy,” says Agha. “I couldn’t continue as I was, knowing there was an alternative.”

It was not a decision Agha took lightly. “Singing is a huge part of my life, and it’s part of my identity," says Agha. "It’s who I am. So to think about not being able to sing the same way anymore was incredibly scary.”

Part of what motivates the pair in their research is the hope that other transitioning singers will benefit from Agha’s experiences. “So many folks worry about transitioning because they don’t know what will happen to their voices,” says Agha. “They're living with tremendous dysphoria because they don't want to risk their voices. So we’d like to have more information to share. I can’t just say, ‘Go for it; you'll be fine.’ We don't know that.”

Hynes adds that many who transition often simply stop singing as they undergo testosterone therapy. “The voice becomes unstable or hoarse, or it starts cracking,” she says. “And you may not feel you can manage that.”

Agha’s voice has changed substantially in the two years since they started taking testosterone. “My overall range has only shifted down a fourth,” says Agha. “It’s a really small difference.” However, the changes in tone and quality have been dramatic. “My high notes are darker and richer and I have more power and capacity in the lower part of my range.”

While Agha has been challenged by instability and lack of control in their voice, those seem to be temporary and have improved over time and with practice. Agha has also found that their voice gets tired more quickly now. “I can’t get through a full choir rehearsal now,” says Agha. “I have to take breaks. And that is really frustrating.”

Hynes and Agha plan to share their research findings through the usual academic means, by publishing articles in scholarly journals. But they're also getting creative about knowledge sharing. An interdisciplinary social justice concert, incorporating solo singing, choral music, documentary film and storytelling is in the works for September, 2019.

“The concert will bring science and art together to share how Ari’s voice changes, to celebrate a supportive transition experience, and explore connections between voice and identity,” says Hynes. The concert will feature Hynes and Agha and will incorporate some of the audio and video collected during their research. In addition, they've commissioned new pieces, and plan to partner with local LGBTQ organizations to highlight their work.

“I see musical performance as a form of activism,” says Hynes. “With this project, we’ll be using music as a springboard to ignite action on the part of the audience — perhaps changing attitudes or discomfort with unfamiliar gender pronouns or hopefully deepening their engagement with transgender advocacy.”

Hynes and Agha intend to choose their repertoire in a very deliberate way. “We’ll be sending out a particular message,” she says. “So we’ll choose pieces that ask certain questions of the audience. When you’re faced with these questions about someone else’s human experience, how will you react?”

Music, according to Hynes, is unique in its ability to motivate and inspire. “Through music, we have an opportunity to express information in a way that genuinely touches people. This sort of emotional impact is very different from the response you get when you read, say, statistics. Stats are important too, but music can play a fundamental role in building empathy for others.”

Hynes also sees the concert as a way to elevate new voices and push back against some of the misogyny and gender discrimination that has traditionally resided in the classical music industry.

“Many opera characters are still portrayed with rigid gender stereotypes, rather than questioning or changing those narratives. The companies working to challenge archaic frameworks are doing great creative work and bringing opera back to life!”

Hynes sees the social justice concert and research project, called The Key of T, as a chance to change the way the classical music industry treats women and genderqueer musicians. “I like the idea of taking a conservative industry and turning it on its head. I want to ask, how can I use my voice to advance social progress?”

It’s hard to say whether genderqueer stories and performances act as mirrors, windows or springboards. Narratives, research and performances that challenge racial, sexual and gender stereotypes may lead to the embracing of new ideas, to new hope, or new inspiration.

If an Indigenous reader sees himself in Jonny Appleseed, perhaps he will feel bolstered by this powerful reflection. If a transitioning singer discovers the story of Agha and Hynes, perhaps they will be inspired to raise their voice to new heights. And if a student in Mason’s literature class recognizes herself in Heather Has Two Mommies, perhaps she can embrace the multiple facets of her own gender identity.

Hynes, Agha, Mason and Whitehead offer new lenses through which to see the world — lenses that may lead to acceptance. But growing acceptance is not a simple process — in part because acceptance doesn’t grow evenly across a diverse society. “We’re still living in a time where it doesn’t necessarily get better for everyone, because of race or class or gender,” says Mason. “So we still need to be having conversations about acceptance and gender; we can’t stop fighting.”

– – – – –

Participate in a research study

Joshua Whitehead is a doctoral student in the Department of English in UCalgary's Faculty of Arts. After he started graduate studies in Indigenous literature at the University of Calgary, he had his debut poetry collection, Full-Metal Indigiqueer, published by Talonbooks in 2017. His debut novel, Johnny Appleseed, was published by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2018.

Dr. Derritt Mason, PhD, is an assistant professor of English at the University of Calgary, where he teaches and researches at the intersection of children’s literature, queer theory, and cultural studies. His current book project, forthcoming from the University Press of Mississippi, explores the emergence of queer themes in young adult literature and culture. Derritt is also currently co-editing, with Kenneth B. Kidd, a collection of essays that examines summer camp as a queer place and time. Read more about Derritt

Dr. Laura Hynes, DMA, is an assistant professor of voice in UCalgary’s School of Creative and Performing Arts. Laura is committed to to innovative recital programming, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the creation of new works. Read more about Laura

Dr. Ari Agha, PhD, (Sociology) works as a Research Social Planner conducting public policy and program evaluation research for The City of Calgary. Ari advocates feminism, anti-racism, and trans rights, and blogs at www.genderqueerme.com.